Cheyenne Johnson

Staff Writer

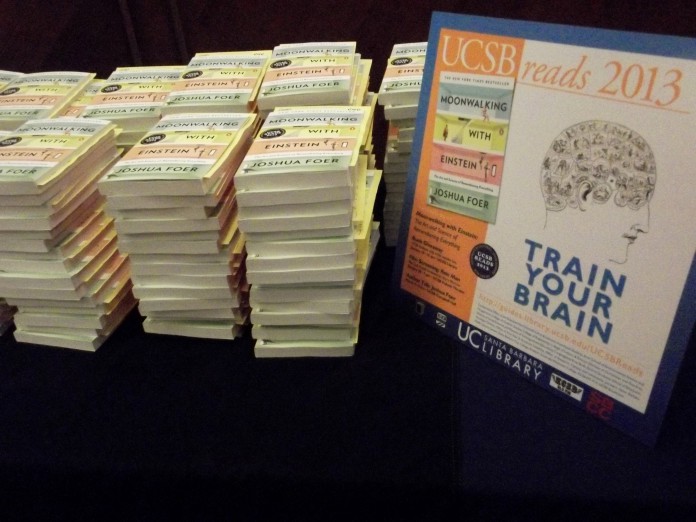

Photo by Cheyenne Johnson

Pope Benedict XVI found himself kicked in the groin and Michael Jackson captured his flatulence in a balloon within the first page of Joshua Foer’s “Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything,” a New York Times Bestseller and the book chosen for UCSB Reads 2013. The novel follows its author, a freelance journalist who says his memory is “nothing special,” as he moves from watching the U.S. Memory Championship to competing in it a year later. Throughout the novel, Foer examines how society has migrated away from a good memory being a necessity and a sign of intelligence to it just being a useful attribute and a clever party trick, particularly when one can remember and recite the order of two shuffled decks of cards after only seeing them once.

The U.S. Memory Championship involves four events that Foer individually practiced for: the Names and Faces event where “mental athletes” have 15 minutes to memorize 117 color photos of random peoples’ profiles, and the Speed Numbers and Speed Cards events where competitors have memorize and recall 500 numbers in under five minutes and a single pack of 52 playing cards as fast as they can. The last event, generally considered the most difficult, is the Poetry event, for which competitors must memorize and repeat an unpublished poem none of them have ever heard before. To say this is a daunting task is letting Foer off easy.

But while these competitions seem entertaining, albeit slightly odd, to modern society, Foer argues that though iPhones and computers have replaced our need to remember, they should not completely dominate our memories.

“Now more than ever,” said Foer, “as the role of memory in our culture erodes at a faster pace than ever before. We need to cultivate our ability to remember. Our memories make us who we are. They are the seat of our values and source of our character. Competing to see who can memorize more pages of poetry might seem beside the point, but it’s about taking a stand against forgetfulness, and embracing primal capacities from which too many of us have become estranged…memory training is not just for the sake of performing party tricks, it’s about nurturing something profoundly and essentially human.”

The book does its part to reveal the culture behind memory and the emphasis society used to put on it. One of the most interesting relationships Foer examined was that between memory entirely recovered from the mind and, upon the existence and widespread use of writing, memory encouraged by book and texts. While, as a journalist, Foer obviously cannot criticize the invention of writing and its acceptance by society, he can join in concern with Socrates and Thamus, the king of Egypt who, when offered the gift of writing by the Egyptian god Theuth, was reluctant to accept since “if men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls.”

Considering how often I forget my boyfriend’s number simply because it’s in my phone, Thamus may have been on to something.

The book is a quick read, perhaps counter to its main message that memory comes from paying close attention and not reading a page a minute while on an elliptical at the gym. The simpler memory devices like the memory palace and turning names into images (Reagan become ray gun) will likely stay with readers, at least as an interesting thing to try at parties. More complicated methods, like the one used to remember long strands of numbers or a deck of cards, probably won’t extend past the book—if the reader bothered to learn the techniques at all.

Overall, though, the novel is interesting and informative, introducing its readers to a world and a set of techniques long overlooked and in theory replaced by modern technology. For anyone sick of Post-It notes littering their desk or tired of forgetting what that one person at that one party was called, I recommend taking a quick moonwalk with Joshau Foer and Albert Einstein. Your mind will thank you for it.