Serena Lee

Staff Writer

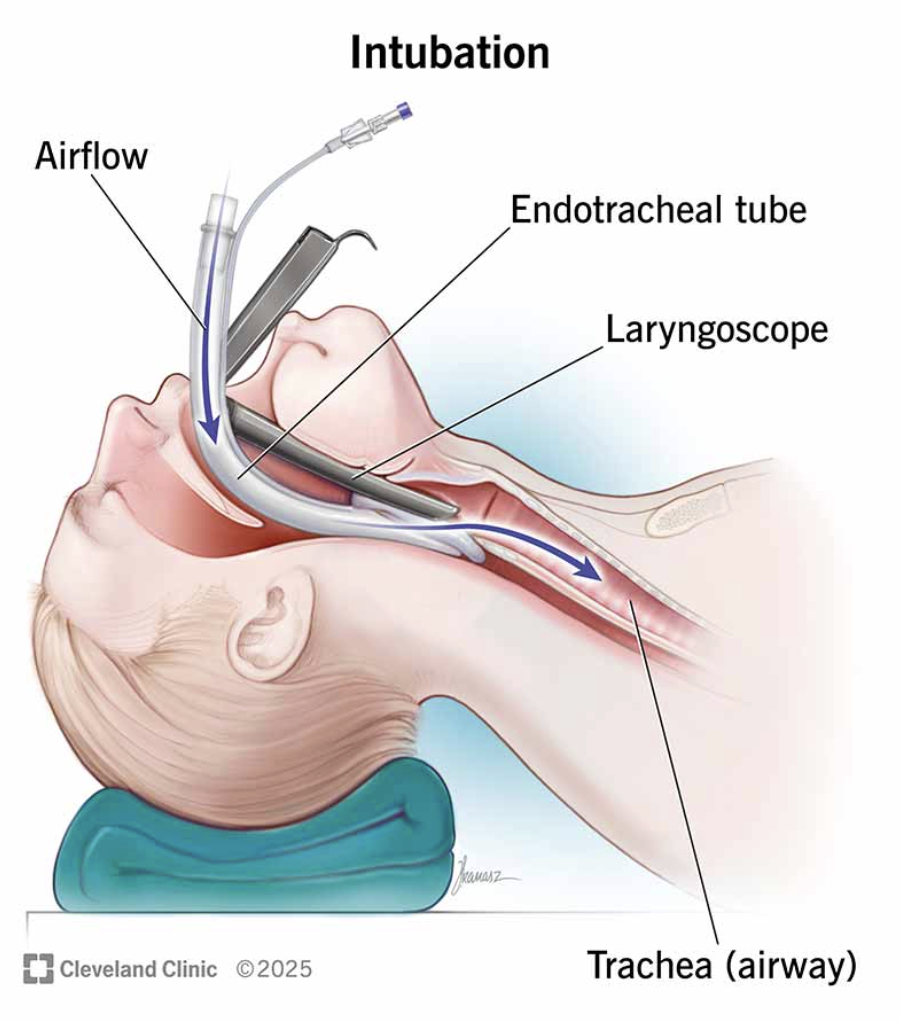

Every year, over 650,000 intubations are administered outside of operating rooms in the United States to deliver life-saving oxygen into patients’ airways. Yet, complications arise from standard procedures involving laryngoscopes, medical instruments used to view the larynx and vocal chords during intubation. These can injure the surrounding area at best, or fail to secure the airway at worst. But what if there was a more intuitive way to intubate with near-perfect precision in just under half the average time?

In an interview with The Bottom Line, Dr. David Haggerty, a recent Ph.D. graduate from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) and founder of biotechnology startup Vine Medical, walks us through his development of a novel soft robotic intubation device that accomplishes exactly that.

Q: What motivated you to apply your soft robotics expertise to medical-related applications such as intubation procedures?

A: I’d always known I wanted to get into medical technology for a variety of reasons, but just a few months before learning about this problem and its severity, my cousin got in a motorcycle accident and passed away. A couple months later, a physician from Stanford reached out to us about how bad the airway management problem is outside hospital environments, which appears to be a primary contributor to unnecessary morbidity and mortality. It seemed like I had the skill set and interest, and there was this need in the world uniquely relevant to me. And so, it was kind of a perfect match.

Q: What were the biggest technical challenges you faced in development?

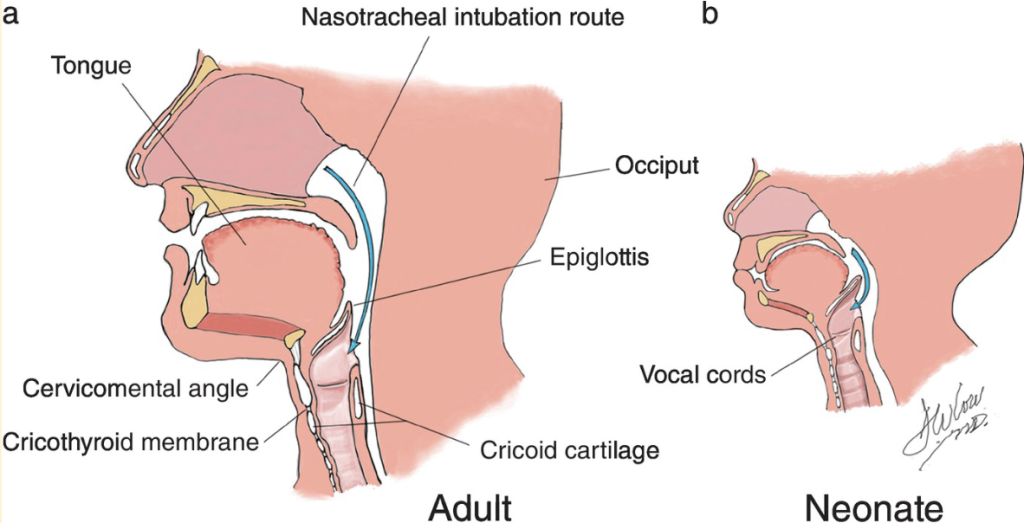

A: The biggest technical hurdle was trying to build a device that not only overcomes the evolutionary barrier to keep the airway clear, but one that also adapts to different anatomical variations of the human airway in a single package. This has led to many hours in the cadaver lab and hundreds, if not thousands, of different iterations.

Q: Are there anatomical variations (e.g. smaller airways in infants) that you anticipate this robot can better adapt to in comparison with standard laryngoscopes?

A: The great thing about our technology is it’s well-suited to that adaptation: we can go a lot smaller in scale. The neonatal nasal anatomy is more anterior and there’s a longer epiglottis. You have to create a pretty sharp geometry to get into the trachea. That’s what’s challenging for traditional push-from-the-base, rigid tools like laryngoscopes. When you grow, however, it is quite simple: You can tune the trajectory that you want your device to take relatively easily. We’ve made prototypes for different scales, but in the paper, we really wanted to show the power of a soft robotic solution in which a low-skilled practitioner with little experience with the device — without the aid of visualization — can still intubate with high reliability.

Q: In contrast to traditional laryngoscopes, your device has a tip extension that unfolds as it enters the endotracheal tube, which was inspired by those found in living organisms like fungal hyphae. How did you come up with this biomimetic design?

A: I have to give a lot of the inspirational credit to my Ph.D. advisor, Professor Elliot Hawkes at [UCSB]. He is the real mastermind behind the innovation that is the vine robot. He was the one who first asked, “There’s this vine on my desk. It’ll find light, it’ll grow over obstacles, it’ll grow through small gaps. But how does it do this? Can we mimic this?” And it was from that insight that he developed the chassis of the device we now call the vine robot.

Q: This work requires knowledge of soft robotics, tracheal anatomy, and the human biological response during these procedures. What does collaboration look like for these projects?

A: It takes a village and it will always take a village to really do anything meaningful in the world because…the richness of any real problem is greater than any one person can have sufficient expertise in. Our successes today were only possible through a collaboration between myself, Dr. Hawkes, and an anesthesiologist from Stanford who brought this issue of emergency airway management to our attention. Then we added an otolaryngologist — an airway upper neck anatomy expert — more anesthesiologists, emergency medicine doctors as well as paramedics. And this is just on the technical development side. This is nothing about regulatory navigation, because the [Food and Drug Association (FDA)] is a key stakeholder here. And so, you cannot get away from the need to collaborate.

Q: How do innovators like yourself balance your expertise in a specialized field with more unfamiliar, technical knowledge that these projects often require?

A: I think that in any new endeavor, you have to start out with humility. There’s a fine line between having confidence in your capability, but humility in your ignorance. You also start using the scientific muscles that one develops through grad school or an advanced degree, which begins with the hypothesis generation process of identifying what you know and what you don’t know. And so, I think the most important thing is a bias to action and a readiness to admit your ignorance in the face of a novel, unclear intellectual landscape.

Q: What are the next steps for this prototype, whether that be making improvements, scaling for distribution, and actually implementing it in healthcare settings?

A: One augmentation we will make is adding a visualization system so that the device has visual, in addition to tactile, feedback. To be used in live patients, we have to run a big volume of testing to ensure device compatibility with human tissue, like checking for anaphylactic responses and making sure it’s safe for human use. Afterwards, we’ll need to run a couple months of human clinical trials for FDA review. Conceivably in everyday medical settings, this technology should be accessible in a little over a year’s time. We hope that we can partner not just with big academic medical institutions in California and throughout the United States, but also locally with Cottage Health to impact patients’ lives just down the street.