Abigail Lim

Science & Tech Editor

For the average culinary enthusiast, “toxins” and “food” in the same sentence may cause alarm. But neurotoxins are present in our daily diets. We interact with these compounds often, and, much like the composition of the air we breathe, we are typically unaware of when certain toxins enter our bodies. However, many people and cultures have learned not only how to avoid them but also how to manage neurotoxin-inclusive lifestyles.

Neurotoxins are a wide class of chemical substances that disrupt the nervous systems of organisms. They vary in severity and extent of damage done to the brain, spinal cord, and nerves. In humans, excess exposure to these substances can lead to neurotoxicity, also known as nervous system poisoning. Because the nervous system is responsible for transmitting signals to and from the brain and other body parts, basic functions like movement and heartbeat may be affected.

At the chemical level, the communication between the mind and body is facilitated by neurotransmitters. Similar to neurotoxins, neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that bind to specific proteins (receptors) within neural (nervous system) cells. The transmitter-protein binding triggers a response in the cell to which the protein belongs, sending a signal to contract a muscle, release a hormone, etc. These signals can be excitatory or inhibitory, meaning they either promote or prevent the generation of an electrical signal. This is often where neurotoxins come in, because they can encourage or block the release of neurotransmitters and thus influence whether or not they can bind to receptors. They can also bind directly to receptors located on the cell to physically prevent the normal neurotransmitter from connecting. Because the balance of basic ions — calcium, sodium, potassium, and chloride — are essential to proper cell function, neurotoxins also change individual cell health. If the functions of many cells are negatively influenced by these irregular compounds, then overall nervous system signal transmission may be hindered.

Despite their reputation for potency, neurotoxins exist for a reason. As a result of natural selection pressures, many organisms produce their own chemicals that are harmful to their specific predators. For example, Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is a small-molecule toxin found in many taxa, and is the most toxic non-protein substance known to science. It is commonly found in rough-skinned newts that reside in Northwest America, which developed this neurotoxin to aid in protection against predators like snakes. Ingestion of TTX, even for humans, most often leads to paralysis or death. Some organisms evolved this mechanism for hunting, self-defense, and reproduction.

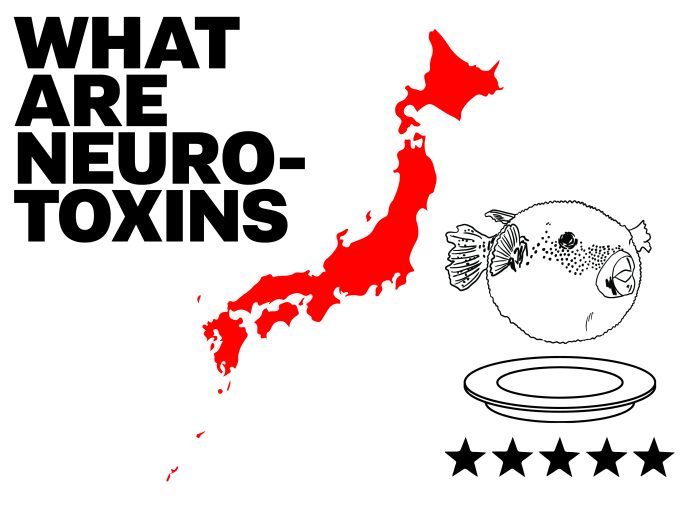

Yet humans sometimes choose to consume plants and animals known to produce neurotoxins. Pufferfish, for example, is a delicacy in professional sushi shops around the world inspired by Japan’s high-profile culinary tradition. However, many of the horror stories of its consumption (that feed into the thrill some seek by eating it) have been highly exaggerated. Tales of influential political figures being assassinated with pufferfish poison, as well as unsuspecting businessmen falling ill after a sushi dinner, have propagated these misconceptions. According to Kaz Matsune, however, from 2004-2013, there were only 12 pufferfish (fugu in Japanese) consumption-related deaths in Japan. As Matsune argues, “These numbers are incredibly low compared to the thousands of deaths caused by foodborne diseases in the United States each year.” And fugu may be safely eaten if properly prepared. Only certified sushi chefs, who have trained for years supervised by field experts, are allowed to handle the fish in a restaurant capacity. This level of responsibility and exclusivity also makes pufferfish a cherished food for its cultural and historical significance to Japan.

Packaged and processed items, which health officials typically recommend people to avoid for their low nutritional value, may also contribute neurotoxic chemicals from preservatives or plastic wrappers. College students in particular may benefit from cutting out instant ramen, chips, convenience store snacks, and brand-name candies. Substituting these items for nutritious alternatives like vegetables and hummus or fruit salads can cut out the added neurotoxins from plastics.

While some neurotoxins can be found from ultra-processed foods, most are naturally-occurring. Aquatic organisms, such as shellfish, sometimes contain algal toxins produced by freshwater and ocean algae. Large fish are also more likely to contain higher amounts of mercury. Furocoumarins are stress toxins released by parsnips, citrus plants, and celery roots that can cause gastrointestinal problems, but many of these plants are used medicinally. A popular food, chili peppers, contains capsaicin, an irritant that triggers pain receptors. For many cultures and civilizations, spice is a key component of their gastronomic heritage and poses little health risk other than the occasional upset stomach. Most people can properly enjoy neurotoxin-containing foods by understanding the associated health risks and avoiding overconsumption.

Though their existence may sound concerning, managing exposure to neurotoxins works much like consuming any other unhealthy food or drink: moderation is key.