Staff Writer

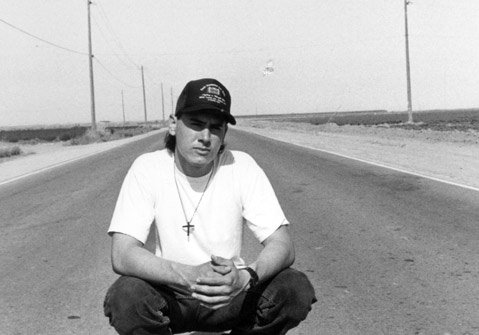

Photo by Radio Bandido

Eighteen years after the death of a well-known Chicano activist and student, a new documentary brings some light to the mystery surrounding his death. In November 1994, University of California Davis student and KDVS-FM Chicano radio activist Oscar “Bandido” Gomez was found dead on the east side of the University of California Santa Barbara campus by Goleta Beach. The local authorities wrote it off as an accident, despite evidence that there may have been foul play, indicated by the blunt-force trauma on his head and reports of a fight with his friend, who happened to have been the last person to see him alive. The case was controversially closed by the Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Office; yet the questions of his friends and family remained unanswered.

Filmmaker and friend of the victim, Pepe Urquijo, dedicated several years to his search for truth, armed only with his camera and a hunch that an important piece to the puzzle was missing.

KCSB-FM presented a preview screening of Urquijo’s documentary “Radio Bandido,” the long-awaited product of his investigation, on April 11 as part of the station’s “Popped Culture” film series. “Radio Bandido” is a compilation of various archival materials, photos, home movies and most prominently, interviews of the activist’s friends, families and others related to his life and work. Director Urquijo was present for a Q&A session after the screening.

The first scene of the documentary is shot from an underwater perspective in the ocean, which can be interpreted as Gomez’s last living sight. This eerie shot starts the film off with a ghostly feeling, right off the bat. This otherworldly connection is maintained by Urquijo’s narrative commentary throughout the film, which consists of an ongoing conversation with his deceased friend.

“Gomez’s story is missing an ending,” says Urquijo, in the film. “I know the truth is out there, I just gotta find it.”

Urquijo’s one-sided questions are mostly answered throughout the film by audio footage of Gomez’s radio broadcast on “La Onda Chicana,” the radio program through which he kept an ongoing discourse with his listeners and rallied his people, “La Raza,” to celebrate their history, pride and culture, especially in the face of opposition.

“Oscar showed the young Latino/Chicano students in his community that they can be cool, they can be down to earth and they can be educated,” said an audience member who knew Gomez personally.

Urquijo concludes his documentary and imaginary conversation with Gomez by saying, “I was only able to tell your story because you touched their lives.”

Many of those featured in the film were present for the screening in Pollock Theater, and contributed greatly to the powerful discussion with students and other audience members about the political climate that surrounded Gomez as a student, as well as the parallel between him and students today.

Eddie Salas, a friend and colleague of Gomez at KDVS, spoke about what he believes the film’s call to action is.

“The issue is that fees are going up,” said Salas. “The issue is that Oscar Gomez might not have been able to go to the University of California, and a lot of other working class people would not be able to access the University at all. That’s what’s happening now, and if we forget that, then we’re not doing justice to Oscar.”

In support of Gomez’s educational activism goals, The Latino United Community and Higher Education Association, a group of Baldwin High School alumni, now offers a scholarship in memory of Gomez. The LUCHA Foundation believes tuition costs should not be an obstacle for a student’s higher education plans.

Another attendee at the premiere, Professor Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval of the Chicano Studies Department at UCSB, provided some context for Salas’ qualms about the UC system.

“In 1993 the UC Regents decided to increase fees by 40 percent,” said Armbruster-Sandoval. “In 2009 they decided to increase fees by 40 percent again.”

Armbruster-Sandoval also explained the growing turmoil at UC campuses that led to four hunger strikes in the early 1990s. The strike at UCSB in 1994 is what brought Oscar Gomez to the area. Professor Armbruster-Sandoval said his curiosity about the mysterious circumstances surrounding Gomez’ death is what brought him to the film screening.

“Was he drunk?” asked Armbruster-Sandoval. “Was he pushed? Was he a political activist and so somebody wanted to kill him because he was a troublemaker like Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez or Gandhi that people wanted to get rid of? [Urquijo] came up with some really interesting theories about the resolution of the case.”

“Frankly I’m really mad and saddened by the fact, and also kind of inspired. It just seems like something stinks about this,” continued Armbruster-Sandoval. “Something isn’t right, and I think they hushed it up to a certain degree. It may prove to be the case that it was an accident, maybe he was drunk and fell down-doesn’t seem like that though. It seems like something much, much deeper is taking place.”

In the end, Pepe Urquijo’s investigation turns out to be inconclusive, however the spirit of the “Bandido” is immortalized in film.

“It’s different for everybody, but to be a ‘Bandido/a’ is about going against the norm, doing what you need to do, and bringing it back to the community, and Oscar exemplifies that,” said Urquijo. “He found a passion with his microphone, with music, and he brought those two things together better than anyone’s seen in a really long time.”