Janani Ravikumar

Staff Writer

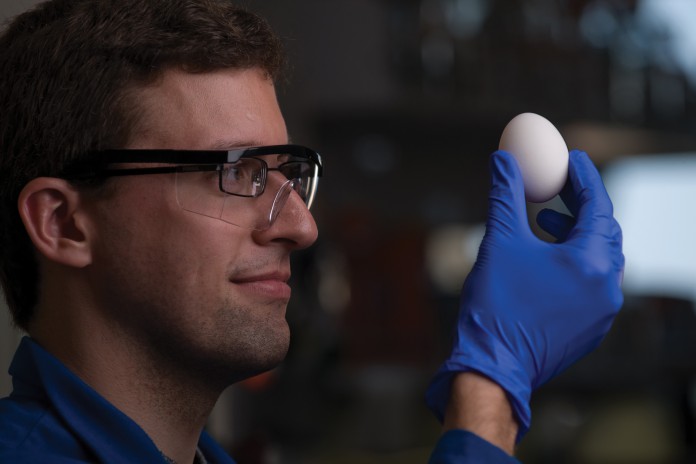

Photos courtesy of Steve Zylius | UCI

While it remains impossible to unring a bell, it is now possible to unboil an egg, as chemists at University of California, Irvine have discovered how to unboil egg whites by manipulating proteins.

“Yes, we have invented a way to unboil a hen egg,” said UCI chemistry and biology professor Gregory Weiss, according to UCI’s press release. “In our paper, we describe a device for pulling apart tangled proteins and allowing them to refold. We start with egg whites boiled for 20 minutes at 90 degrees Celsius and return a key protein in the egg to working order.”

According to the Los Angeles Times, when an egg is boiled, the protein in the egg white changes shape from tightly wound individual clumps to long, tangled strands.

In order to unboil an egg, a clear protein called lysozyme must be recreated. To accomplish this, Weiss and his colleagues add a urea substance that chews away at the whites and liquefies the solid materials. In the other half of the process, a vortex fluid device—a high-powered machine designed by Professor Colin Raston from South Australia’s Flinders University—applies microfluidic films to tiny, unusable, balled up protein bits, forcing them back into their proper form.

Proteins are long polymers made of amino acids. Shaped in a right-handed spiral coil, proteins can misfold spontaneously when following the wrong pathway and change into a toxic configuration. By unboiling eggs, the chances of proteins misfolding are greatly shortened.

“They’re like little elastic beads,” Weiss said, according to Washington Post. “This stretches and unstretches them, and gives them their shape back.”

By quickly and cheaply reforming common proteins from yeast or E. coli bacteria, protein manufacturing could become streamlined, and cancer treatments could become more affordable.

“It’s not so much that we’re interested in processing the eggs,” said Weiss to the Los Angeles Times. “That’s just demonstrating how powerful this process is. The real problem is there are lots of cases of gummy proteins that you spend way too much time scraping off your test tubes, and you want some means of recovering that material.”

Currently, for cancer research, scientists use expensive hamster ovary cells because the proteins in these cells are not likely to misfold. This new process could save much of the 160 billion that cancer researchers spend on proteins each year, according to the Los Angeles Times.

“The new process takes minutes,” said Weiss. “It speeds things up by a factor of thousands.”

This process could also benefit industrial cheese makers, farmers, and others who use recombinant proteins.

“I can’t predict how much money it will save,” said Weiss, according to The Guardian, “but I can [predict] this will save a ton of time, and time is money.”

Weiss and his colleagues have published their findings in the journal ChemBioChem. UCI has also filed a patent for the work, and its Office of Technology Alliances is currently working with interested commercial partners.