Deanna B. Kim

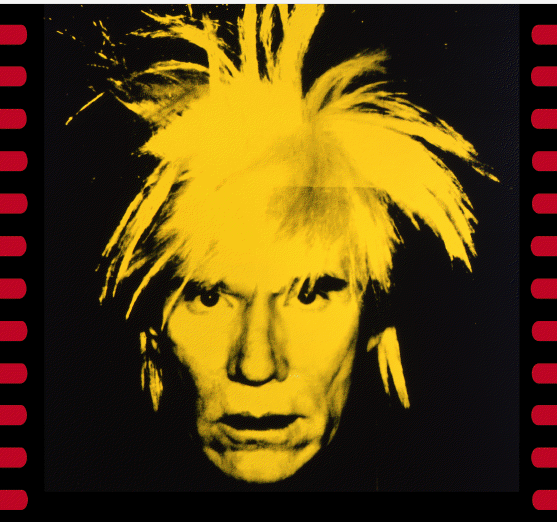

Photo Courtesy of Warhol Promotional Materials

Andy Warhol is a man most renowned for leading the American Pop Art movement with his platinum blonde hair, nautical stripes and unconventional artistic flair. His five-year period dabbling in film, however, is something that may come as a surprise to many. Not only did Warhol change the face of Marilyn Monroe and the Brillo Box, but he also produced around 650 films in a span of five years. Four hundred seventy-two of these films are silent, black and white film portraits or screen tests. Warhol locked his films away from distribution in 1970 and his films only recently became available to the public, thanks to The Whitney Museum of American Art and The Museum of Modern Art.

The lesser-known side of Warhol was showcased at the first part of Pollock Theatre’s Andy Warhol Film Series on Wednesday, Sept. 10, where Warhol’s film “Screen Tests” made its debut. “Screen Tests” features many avant-garde artists, musicians, writers, actors, actresses, dancers and models such as Edie Sedgwick, Imu, Paul America, Lou Reed, Nico and Bob Dylan. Using 16 mm film, Warhol showcased each person anywhere from 3.8 minutes to 4.6 minutes. Some remained completely still and transfixed at the camera, while others would squirm and fidget in the spotlight.

The screen tests were originally shown at Warhol’s New York studio, The Factory, in complete silence. To fill the aural void, Dick Hebdige, an art studies professor at the University of California Santa Barbara’s and the director of the campus’ Interdisciplinary Humanities Center, prepared a playlist to accompany the screen tests; he admitted with a laugh that the music was contrived together last minute.

The exposition of the film was accompanied by Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” as Edie Sedgwick gazed into the camera with her alluring and captivating doe eyes for 4.5 minutes.

The song was delightful and complementary to the screen test, especially considering that “Like a Rolling Stone” is rumored to be about Sedgwick and Warhol.

It was a bit uncomfortable at first, gazing into the faces of daunting, massive black and white faces, but as each screen test appeared and faded away, I quickly felt awe of Warhol’s work. It was like staring at one of his works of pop art and admiring it for its unconventional simplicity and originality. Only this time, Warhol had full control of the audience, telling us what to look at and for exactly how long.

I could see why Warhol aroused so much controversy. His work was so simple—too simple, it seemed—and purely superficial. He pretty much had celebrities sit in front a camera and remain still or natural for a couple minutes; even the screen changes were choppy. Yet, his work remained hypnotizing. It was refreshing that I only needed to use my most basic senses to view the clips, where I did not have to think about a story line or fictional people. The only factors I thought about were the aesthetics of each person displayed and their influence in the entertainment industry and culture of that time. Their mannerisms, face expressions and occasional drag of cigarette were completely mesmerizing.

The playlist itself was great and a pleasant artistic spin for Screen Tests, but after awhile I felt it took away from the original technique of silence. Professor Hebdige seemed to have read my mind, because partway through he began to turn the music on and off. This enabled the audience to enjoy the screen tests both in their original state and with good music. Some of the songs did enhance Warhol’s films as the vocals and melodies took us back to Warhol and his friends’ reign over the 60s, but in hindsight I wish that the majority of the film portraits were displayed in complete silence. I did, however, thoroughly enjoy Queen’s “Fame” and The Velvet Underground’s “I’ll be Your Mirror” and “Oh! Sweet Nuthin’.”

It was during those moments of complete silence, when I could only hear the reel of film sputter in the back, that the clips truly began to speak for themselves. There was no color, no noise and no distraction from the raw energy and beauty of each person captured by Warhol.