Madeleine Kirsch

Writer

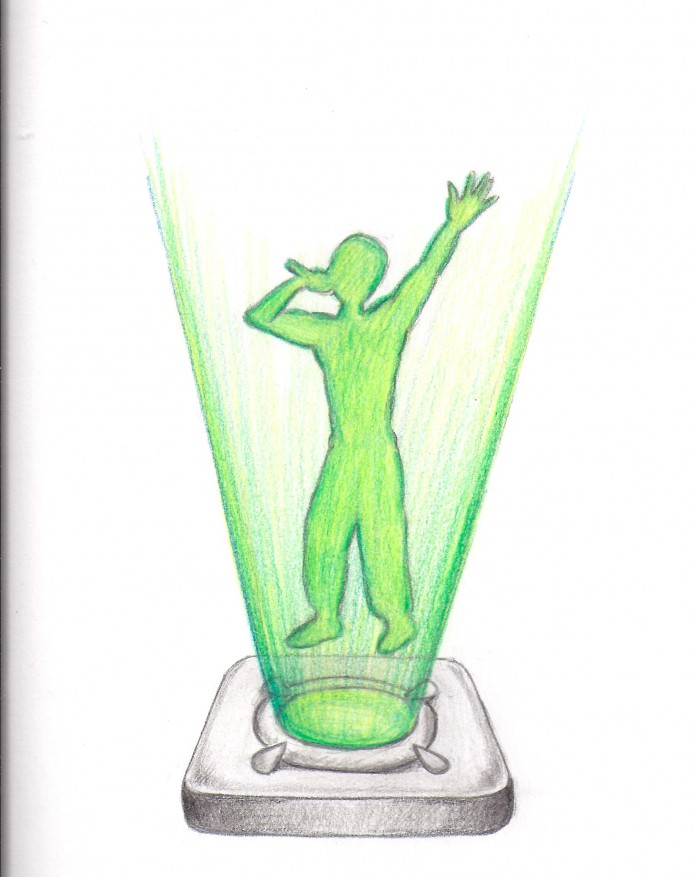

Illustration by Irene Wang

Tupac Shakur, who was killed in a 1996 Las Vegas shooting, sprang back to life Sunday evening, April 15 for the unique enjoyment of drugged-up Coachella goers and intrigued YouTube searchers. His form of reincarnation: an astonishingly realistic hologram.

Although hologram Shakur’s target audience may not have represented the pinnacle of high society, this kind of technology could have more serious implications in fields outside entertainment. Imagine, for instance, attending a presentation given by a digitally rendered historical figure. And why stop there? One day you might be able to have lunch with the hologram of your dead grandmother.

Unfortunately, critical reaction to the Coachella hologram’s performance has not been so optimistic. Most have written the technology off as some cheap trick that will be used to make new money off of old acts, analogous to how the film industry ignited the 3-D movie trend. Suddenly, old classics are being repackaged with the 3-D label and Hollywood is double-dipping on profits, so who is to say that musical tour companies couldn’t potentially recreate a holographic Michael Jackson or Elvis Presley and likewise go in for round two, they argue?

But even if the music industry’s motives do turn out to be self-interested and greedy, I dare say that digital reanimation of the deceased is far more impressive than the Titanic popping out of a movie screen (provided you wear the silly glasses; otherwise it’s simply blurry Titanic). And as mentioned previously, hologram technology may be cultivated to fill niches that are more sophisticated in nature. In other words, this might not even be the music industry’s game to play.

As a matter of fact, illusionist hologram-like technology has its roots not in music, but in theater. In a 19th century production of Charles Dicken’s “The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain,” producers reflected the image of a concealed actor on to the stage via an angled mirror, creating the illusion of a ghost figure.

The fundamental idea behind the Shakur creation was essentially the same, but instead of reflecting a living person on to the stage, the crew projected a digitally created character. Animators studied old videos and photos of the singer and synthesized a large amount of data in order to generate a convincing computer persona. Then the computer figure was mirrored onto the stage.

In this manner, hologram Shakur is not the unprecedented technological leap forward that it appears to be, but rather a new take on an old trick. The convergence of several favorable circumstances is responsible for finally bringing the technique into the public eye- namely, the cultural relevance of Tupac, the venue of Coachella and the sharing platform of the Internet.

The hologram was employed at the right place, at the right time and among the right people to catch on, but now that popular culture has brought it to the table, the technology needs to expand into other realms of life. We need to see holographic animations as not just a means to entertain and make a profit, but also as a form of cultural wealth. Realistic depictions of dead people should not solely be exploited for monetary gain, but also appreciated as artifacts.

Holograms could be used in schools to allow students to more intimately watch the Gettysburg Address or Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Imagine having a very life-like Abraham Lincoln as your lecturer.

Eventually the technology could expand to the personal level. We could make holographic representations of our children when they are young and replay them later in life to reminisce. The experience would be more satisfying than a standard home video.

Holographic technology has endless potential and deserves to be considered more carefully. The music industry is only the launch pad.

Comments are closed.