Writer

Photo from apartmenttherapy.com

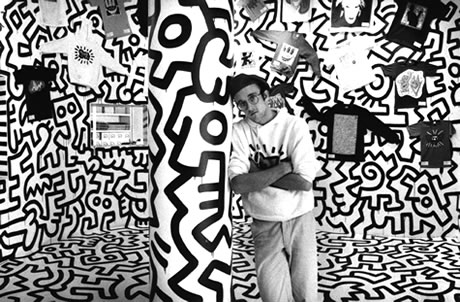

To a non-art major, the name Keith Haring probably does not ring a bell. I confess that before watching the documentary on his life and work, I knew nothing about him. But after watching the film “The Universe of Keith Haring,” I realized that I was more familiar with Haring than I knew. The album covers for the compilation series “Very Special Christmas” that my parents listened to every Christmas were designed by him; many of the t-shirts that Clarissa Darling wears in “Clarissa Explains It All” were Haring t-shirts; not to mention the countless works of art that have been created in his style since. His striking yet simple images permeated popular culture in the 1980s, and still maintain influence and recognition to this day.

In the “Universe of Keith Haring,” we get a chance to learn about the world that shaped Haring, as well as the world he created through his art. Haring was born in a small town in Pennsylvania, where he grew up with a religious upbringing. His father would draw him small pictures as a child, encouraging Keith to be interested in art even at an early age. Keith began experimenting with speed drawing, and was heavily influenced by Disney and Dr. Seuss art.

Although he grew up in a predominantly white small town, he was drawn to the “urban” people he would meet at church. During high school, he began to be involved in the counterculture that existed at the time, and would leave on random hitchhiking journeys.

After high school he moved to Pittsburgh, where he attended the Ivy School of Professional Art, hoping to become a professional graphic artist. However, he soon tired of the commercial aspect and dropped out. He went out to have his own one-man show and exhibition, which was greatly influenced by urban culture and the experiences he had in male bathhouses, what he called “gay paradise.” Despite enjoying some early success in Pittsburgh, Haring longed to move to the mecca of art, New York City.

He eventually made the move to New York and began immersing himself in graffiti culture, which was relatively new and exciting for him. He would take the subway for hours, just to glimpse the graffiti art present in the subway stations and cars. Because of his interest in graffiti art, he became friends with many infamous graffiti artists such as Fab 5 Freddy. Haring began drawing graffiti art on the empty advertisement posters in the subway stations, sometimes drawing as many as 40 guerrilla art scenes a day. The city “became his canvas” and Haring was at the forefront of the alternative art scene in New York City.

Along with his fellow artist friends such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf, as well as other pop culture phenomenons like Andy Warhol, Grace Jones and Madonna, Haring ran exhibits and performances at the Mudd Club and Club 57, which were famous for their “alternative” art shows and live performances. He not only designed but participated in many of these performances. Many of the people in his circle at the time went on to become famous artists, such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and the photographer David LaChappelle.

Just as Haring’s professional life began blowing up–he got to paint the infamous NYC “Crack is Wack” mural, opened the “Pop Shop” in SoHo and participated in various other commercial and public works–he was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988. Although he fought a brave fight, he sadly succumbed to the disease in 1990. He was well-beloved by his friends, who vowed to keep his memory alive through the Keith Haring Foundation.

Even if you are not an art major, I would recommend checking out the rest of the films in the “Art/Architecture” film series, put on by University of California Santa Barbara’s Arts & Lectures Series. The film that accompanied “The Universe of Keith Haring” on the Jan. 15 screening was about his friend and contemporarie, Jean-Michel Basquiat (who is also featured in the Keith Haring film).

The next collection of films in the series is about urban architecture. On Jan. 22, the film “Urbanized” deals with the strategies of urban design, and features interviews with many modern architects and visual thinkers. The accompanying film, “Objectified” has more of an abstract subject; it deals with the relationships we have with manufactured objects, and speaks to the inventiveness of designers in everyday objects, as well as more technically advanced objects. Whether you’re into art or architecture, the films in this series are both informative and interesting.