Ladann Kiassat

Science & Technology Editor

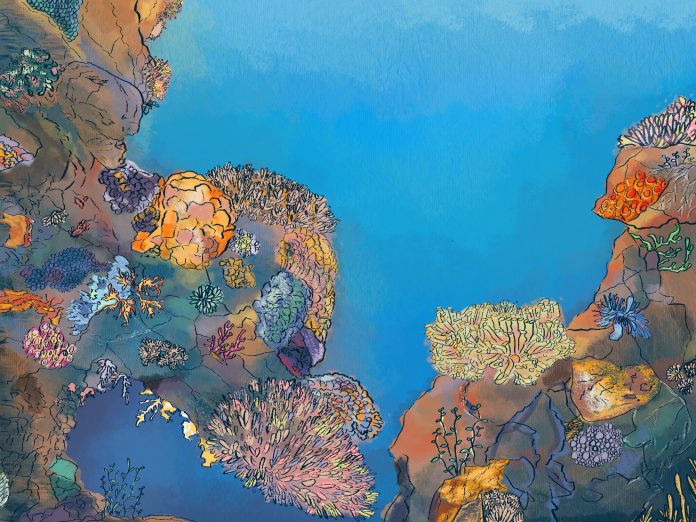

Despite coral reefs’ importance to the ocean’s ecosystem, warming waters, pollution, ocean acidification, and physical destruction are killing coral reefs at an astonishing rate. Our dying coral reefs are a loud and clear call from nature to protect the reefs’ marine life.

A study done by UC Santa Barbara’s (UCSB) Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology (EEMB) department researchers proposes a strategy for saving dying reefs by reducing nutrient pollution.

The team outlined its findings in the scientific journal “Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.” In the absence of beneficial host algae, which die at high temperatures, the coral will eventually die. According to the journal, “[the researchers’] experimental framework represents a powerful diagnostic tool to probe for multiple attractors in ecological systems and, as such, can inform management strategies needed to maintain critical ecosystem functions in the face of escalating stresses.”

Using this tool, researchers investigated the effects of nitrogen on coral bleaching. Coral bleaching occurs when the water is too warm, causing the coral to expel the algae (zooxanthellae) living in their tissues and turning the coral completely white. The team surveyed more than 10,000 coral around the island of Moorea in French Polynesia during a heatwave in 2016. The researchers took samples from Turbinaria ornata, a large algae common on the reefs around Moorea, which provided a record of the nitrogen that was available to the corals in the months before the heatwave.

“The team concluded that high levels of nitrogen pollution cause coral to bleach faster and increases the severity of bleaching.”

In a full press release with The Current, the lead author of the study Mary Donovan — a postdoctoral researcher — stated that “these relationships are very complex,” and change with one organism’s dependency relying on other organisms. “So, studying them at spatial and temporal scales that match those happening in nature is critical to revealing these really important interactions,” she explained.

The team concluded that high levels of nitrogen pollution cause coral to bleach faster and increases the severity of bleaching.

“The research also tells scientists the rate at which global warming increases. This makes changes in climatic shift more apparent and makes weather predictions more accurate.”

EEMB professor Russ Schmitt also commented that “it basically doubles the severity of bleaching.” The study also concluded that the coral bleached at high temperatures regardless of how much nitrogen was in the system, so even just a little bit of excess nitrogen could lead to severe bleaching under moderate heat conditions.

The research also tells scientists the rate at which global warming increases. This makes changes in climatic shift more apparent and makes weather predictions more accurate.

As more studies are being completed, scientists are urging citizens to be more mindful of climate change, in hopes of slowing down the current rate at which our oceans are heating up.

Illustrations by Esther Liu