Gwendolyn Wu

Staff Writer

Illustration by April Gau

I craned my head around Embarcadero Hall, counting how many people had showed up to lecture. Half the class appeared to be there—an impressive turnout. On the day of my midterm, the house was packed.

Most general education classes at the University of California, Santa Barbara are taught in lectures, where hundreds of students (1,049 in 8 AM Biology) sit in cushy seats with half-formed desks in auditoriums like Campbell Hall. Many are asleep, others texting, and some watch the stage intently. A professor speaks into a crackly microphone and gestures wildly at the powerpoint presentation behind him. These classes are accompanied by sections and labs, supplementing the education with TAs who can help students understand what’s going on.

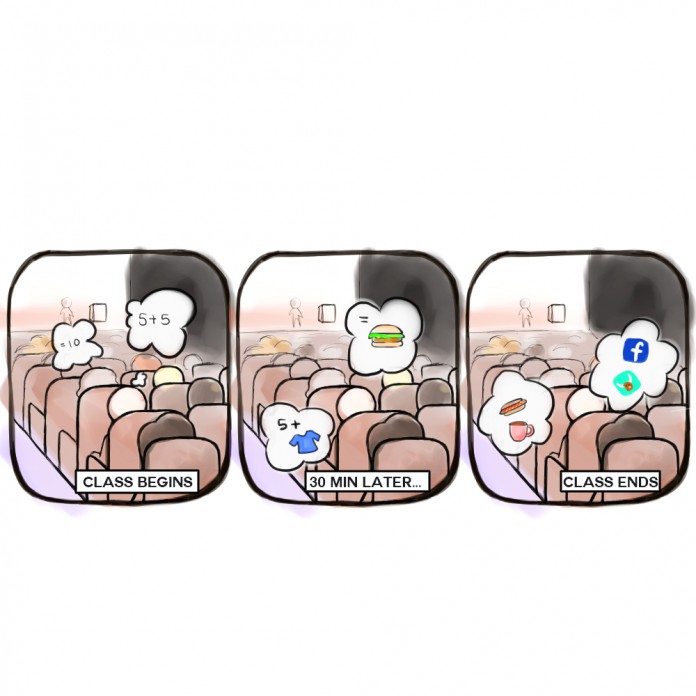

This lecture setup is incredibly ineffective. Students grow distracted as lecture drags on, wondering if this is a waste of time and money. We sit through lectures on history and chemistry, yet don’t retain what professors try to teach us. Is that what we should bear when tuition for the 2014-2015 school year is $12,192 (and nearly triple that for out-of-state students)?

Many students don’t go to lecture if they study from home. Some professors record their lectures and post slideshows online, encouraging many students to “go to class” from the comfort of their bed. Some classes simply repeat the points emphasized in the reading. Why go to class if you can just read and only show up to take exams?

Dr. Robert Samuels, a lecturer with the Writing Department at UCSB, previously taught lectures at University of California, Los Angeles. Samuels talks to students extensively about their experiences as members of these large classrooms.

“The main problem seems to be large lecture classes. Sometimes they can be effective, and I want to stress that,” Samuels said. “I’m not saying all large lectures [are bad]. I’m saying there can be some good ones; I’m saying that there is this tendency [to be less effective].”

Professors try to make their lectures interactive, recognizing the flaws of this method. For example, many use iClickers, asking students questions in an attempt to take attendance and keep them somewhat awake. Others may ask questions aloud, garnering responses from the audience. But only a few.

People don’t absorb the material fully. While some are visual learners and learn through slideshows, for many, lectures aren’t conducive to learning. Attention spans wane; information goes in one ear and out the other. Simply put, it is boring to sit there and apply what you’re learning to the real world.

“There is little opportunity for students to speak and write in classes. Students are trained to passively listen to experts, to be passive citizens,” explained Samuels. “If you spend time being silent, it doesn’t train you to be a democratic citizen. It doesn’t lead to a democratic process [in society].”

Warning bells toll at the prospect of a passive population. It would be reassuring if we could make informed decisions that can change the nation, as a democracy should do. But are we developing that at UCSB? Many professors come here to research, and for some, their talents don’t lie in teaching effectively. If students aren’t encouraged to be active participants in class, it could cause major problems in the future.

If the current system is flawed, what can be done to fix that? Some suggest classes be turned into seminar-style sections. Sections and labs are a good foundation for teaching, although still flawed due to the shortage of TAs and lack of connectivity with the professor. They promote an in-depth analysis of course material and allow students to apply what they’ve learned. Another solution proposes that students capitalize on UCSB’s status as a research university.

“Students, from day one, should be engaged in the research process,” said Samuels. “They should be doing their own research, their own examination of other people’s research, and they should be actively involved in it.”

Should we really stand for exorbitant higher education fees if we aren’t getting the quality of education we deserve? We protest tuition hikes yet never bring attention to the fact that we don’t retain the information we learn in these class settings. Perhaps it’s time to closely examine what’s plaguing the system.

Comments are closed.