Gwen Wu

The current Ebola epidemic is the single most severe outbreak since the initial discovery of ebolaviruses in 1976. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 8,399 people have contracted the virus resulting in 4,033 deaths, with more cases going unreported.

Experts believe that this particular outbreak can be traced back to the death of a two-year-old boy in Guinea on Dec. 6, 2013, and the virus then spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone. Cases have developed in Nigeria, but were contained within their borders by closing off all entrances into the country. Despite precautions, medical missionaries and health workers there have fallen ill.

In July, two American doctors working in West Africa contracted Ebola and were immediately flown back to the U.S. to be treated in special isolation wards. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol were given doses of the experimental drug ZMapp and survived. Brantly was critical of the response from the U.S. in his statements to the media and government.

“It is imperative that the U.S. take the lead instead of relying on other agencies,” Brantly testified at a Senate hearing about Ebola. As of early October, the aid that the U.S. has sent to West Africa consists of military troops and protective gear for workers, but little in the form of medicine.

Controversy surrounds the international community’s response to the epidemic growing in Africa. While NGOs such as Doctors Without Borders responded promptly, criticism centers on how much media coverage has been given to Ebola, but little aid. Critics of the U.S. response point out that the country has been studying Ebola for years, yet clearly have not prepared for an epidemic as seen when researchers depleted their supply of experimental drugs to treat the virus.

“The use of our military is a legitimate and defensible request, because if we do not do something to stop this outbreak now, it quickly could become a matter of U.S. national security–whether that means a regional war that gives terrorist groups like Boko Haram a foothold in West Africa or the spread of the disease into America,” Brantly said. “Fighting those kinds of threats would require more from the Department of Defense than what I am asking for today.”

As far as fighting the threat at home, the federal government will be screening travelers flying from West Africa at five major U.S. airports, according to White House spokesman Josh Earnest. They plan to take temperatures at Newark Liberty, New York’s John F. Kennedy, Chicago’s O’Hare, Washington’s Dulles, and Atlanta’s Jackson-Hartsfield.

This move follows Ebola cases developing in the U.S. On Oct. 8, Dallas patient Thomas Duncan, who traveled to the U.S. from his native country, Liberia, died from the virus. Duncan landed in Texas on Sept. 19 with no visible symptoms, but was admitted to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital nearly two weeks later. Controversy surrounds Duncan’s case, as family members claim he was initially dismissed despite alerting doctors that he had traveled from Liberia. The situation worsened as nurse Nina Pham, who treated Duncan, was confirmed on Sunday to have contracted the virus.

Photojournalist Ashoka Mukpo was flown back to the U.S. on after contracting Ebola while on assignment. According to NBC News, Mukpo is being treated at the Nebraska Medical Center using a combination of an experimental drug and blood transfusion donated by Brantly. Doctors hope that antibodies generated from Brantly’s exposure to the virus will help Mukpo fight the virus.

While many continue to criticize the international response, one thing is clear: something must be done about the epidemic before it spreads internationally.

“It’s a fire straight from the pit of hell,” said Brantly. “We cannot fool ourselves into thinking that the vast moat of the Atlantic Ocean will keep the flames away from our shores.”

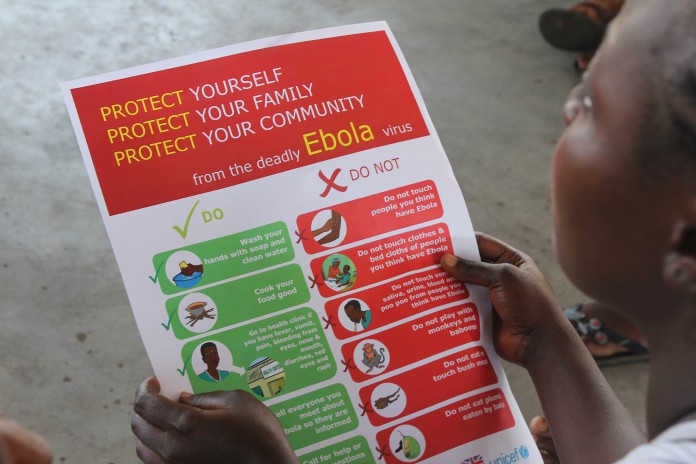

Photo Courtesy of UNICEF Liberia

Comments are closed.