Maddy Kirsch

Staff Writer

Illustration by Madison Mead

Anyone watching cable TV these days knows that America has some fringe interests. We like the Amish, as evidenced by Discovery’s “Amish Mafia,” TLC’s “Breaking Amish,” and National Geographic’s “Amish: Out of Order.” We’re also obsessed with child beauty pageants; 2008 brought about TLC’s “Toddlers and Tiaras,” followed by the 2012 spinoff “Cheer Perfection.” Other trending topics include fundamentalist Mormons (National Geographic’s “Polygamy, USA”), rednecks (A&E’s “Duck Dynasty”), and commercial fishermen (National Geographic’s “Wicked Tuna”), just to name a few.

How on earth did we get here? In the 80s and 90s, networks like Discovery, National Geographic, TLC, and Animal Planet aired nothing but educational shows about science, nature, history, geography, and current events. Then, around the turn of the millennium, they ditched their academic tone and “restrategized” to compete with the reality TV explosion. Out was the raw footage of lionesses hunting and rhesus monkeys copulating, and in was highly-produced, gimmicky entertainment.

Current programming on these networks constitutes a very loose interpretation of their original, educational mission. Animal Planet has stretched the boundaries of what it means to specialize in animals, changing its slogan from “Same Planet, Different World” to “Surprisingly Human” in order to get away with airing more people-based content (read: reality shows).

The devastating result of this reality takeover has been that, apart from a few gems like Discovery’s “Planet Earth” and National Geographic’s “Cosmos: A Space Time Odyssey,” the modern television landscape is largely devoid of quality educational programming.

And even the so-called educational programs that remain are infested with pseudoscience. Discovery’s “Shark Week” used to be about celebrating and respecting sharks, but today it’s just about scaring your pants off with made-up shark horror stories. I guess it’s better to be feared than respected when it comes to ratings.

During the summers of 2013 and 2014, respectively, Discovery chose to air “docufictions” about ancient megalodons supposedly swimming in modern oceans, and about 35 foot-long great whites attacking unsuspecting whale watchers off the coast of South Africa (never happened). The “sharks are beautiful predators” message of Shark Weeks past has devolved into a “sharks are ruthless killers” message –and that certainly cannot be good for wildlife conservation efforts.

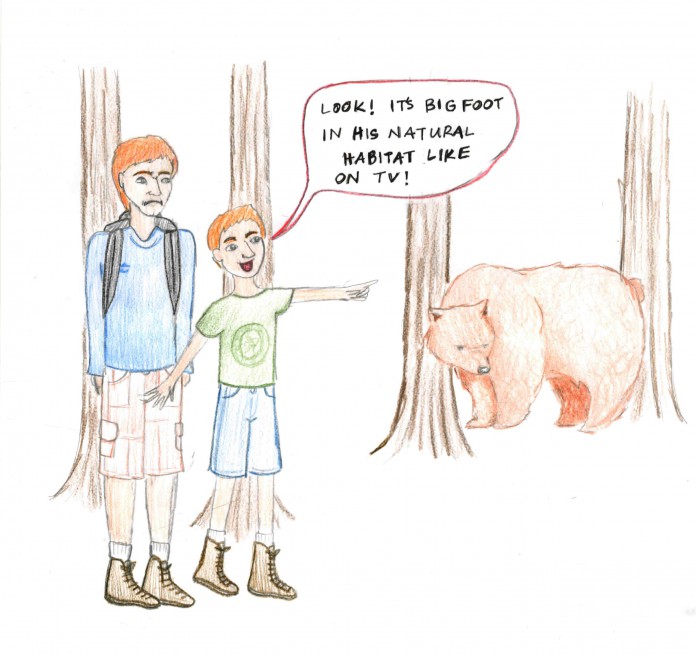

Shark Week is not alone in the docufiction brigade. Shows like “Finding Bigfoot” and “Mermaids: The Body Found” (both Animal Planet) certainly capture audiences’ imaginations, but they present completely contrived evidence, false data and fake “experts.” Disguising pseudoscience as science has dangerous consequences for young, impressionable audiences. The last thing we need is for children to grow up to be ignorant of the scientific method.

Why would a network go to all the trouble of hiring actors to pose as scientists and explain computer generated sequences of imaginary creatures? Why not just have actual scientists explain real footage of animals that exist? The latter option seems cheaper for the network and less misleading to audiences. Win-win, right?

I think the heart of the matter–the reason for the reality/pseudoscience maelstrom on once-credible science channels–is that sensationalism is much easier to sell than honest facts. Only some people will sit for an hour to watch Morgan Freeman narrate fish footage, but almost everyone is curious about mermaids and polygamists. From the network’s perspective, it doesn’t make sense to invest everything in a subset of kids with the attention span for nature documentaries. Bigfoot droppings, ex-Amish teenagers, mermaid fossils, and men with five wives have a certain “wow” factor, and ultimately a much broader appeal.

The new millennium has not been great for science on cable television, but let’s not throw in the towel just yet. Neil Degrasse Tyson brilliantly brought back Carl Sagan’s “Cosmos” earlier this year. It was organically entertaining and even gripping at times, telling real-life horror stories of climate change and the vast scale of the universe. Unfortunately, it can be hard for naïve viewers to sort out real science from the reality/sensationalist noise. Going forward, it’s we the viewers who truly hold the power to sway networks one direction or another, and we need to seriously consider what we value more: education or entertainment.