Maddy Kirsch

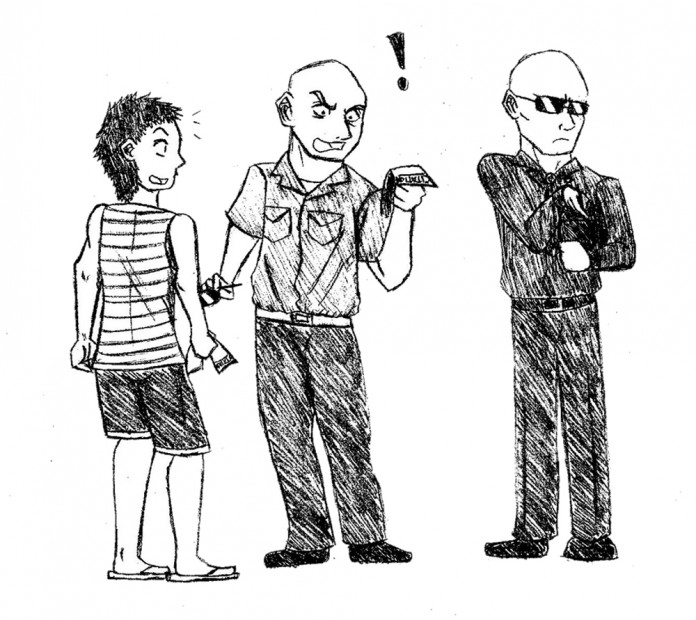

Illustration by Julissa Villatoro

On a recent episode of The Daily Show, Jon Stewart joked about a report that 1 percent of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) workforce owes taxes back to the IRS. “Are you saying that the people at the ‘pay us your taxes’ place don’t pay their taxes?” Stewart asked, and proceeded to suggest that we should hire another IRS–an IIRS, it would be called–to police the first. This, of course, raises the question of who would police the IIRS. We would need an IIIRS, and then an IVRS–and the joke goes on and on.

This tongue-in-cheek play on roman numerals makes an interesting point about the nature of authority. The simplest way to manage corrupt authority figures is to hold the perpetrators accountable to someone else; but in doing so, you’ve given “someone else” an opportunity to be corrupt as well. By this logic, there is no value in policing the police, because then we would also need to find police to police the police’s police.

However, when you personally have to fight a bogus traffic ticket (who knew you’re supposed to stop 30 feet behind a school bus–did anyone measure anyway?) or unfair noise violations (it was 12:01, okay), it sure feels like somebody should be overseeing police and holding them accountable for bad calls.

Isla Vista’s blood certainly boiled a few weeks ago when cops went undercover as college students and infiltrated a house party, issuing several Minor in Possession (MIP) citations. Given that the IV consensus seems to be that police promote “safety, not MIPs,” many residents were upset that officers would go out of their way to get people in trouble. Party-goers felt as though power had been abused, and hosts began posting signs reading “21 and over” and “cops must show badge.”

The incident left Isla Vistans feeling a bit cheated, and many called out the undercover cops on Reddit and Facebook, eventually capturing the attention of local media–The Santa Barbara Independent and Noozhawk published stories about what they called the “Party Patrol.” In the end, all of that kind of sounds like policing the police to me.

I think that law enforcement and other authority figures should absolutely be monitored and held accountable for missteps, but creating additional agencies or organizations to do such monitoring is not going to work out. Instead of policing the police from the top, we should police the police from the bottom–that is, use the power of a free press and a free Internet to expose perpetrators and inspire corrective actions.

This free market-esque way of approaching justice may not get you out of that traffic ticket, but for major abuses of power it works pretty well. Last week, a video of what appeared to be an instance of police brutality in Buffalo, N.Y., went viral on YouTube. The footage showed the victim lying on a sidewalk screaming in pain while up to 4 officers held him down and beat him. The victim continually asked the officers to “please stop” and issued several apologies, but the violence continued. The images sparked public outcry and led to a formal investigation.

This particular video was only the latest in a slew of viral videos exposing police brutality. In response to such shocking images, people are calling for constant police oversight. Some are even proposing that police wear cameras as part of their uniforms so that their behavior can be monitored at all times.

No doubt these officers should be brought to justice if the investigation finds the beatings were unnecessary, but let’s slow down before solving the problem of abuse of authority with more authority. Strapping cameras on officers and holding yet someone else responsible for watching the footage–and making sure the cameras are reliably worn and turned on in the first place–just creates more opportunities for corruption.

Instead, we need to look at the people. The video from Buffalo was a success story in that a witness decided to share suspicious behavior and average people rallied together to demand an investigation. In the age of rapid information sharing, the solution is not more oversight but more sight in general–if average people identify and share abuses of power, we can hold authorities accountable without instating more authorities.

Comments are closed.