Becca Ou

Staff Writer

Photos by Alex Albarran-Ayala

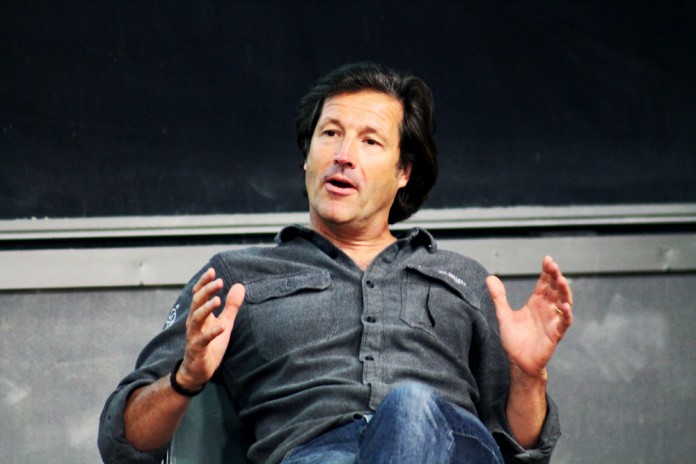

In a panel hosted by the University of California, Santa Barbara Department of Geography on Wednesday, May 21, UCSB Professor Dan Montello, Brian Thompson of Telegraph Brewing Co., David Walker of Firestone Walker Brewing Co., and Zach Rosen, a local cicerone, discussed the craft beer revolution.

On any given college campus in America, UCSB included, familiar beer brands consist of Coors Light and Bud Light. These big beer companies produce a cheap beverage that tastes of the same, watered-down flavor wherever you go. There is a world of beer, however, beyond the cheap cans of underwhelming beer that gets poured into red Solo cups for beer games–beer that even transcends the common alternatives served at college bars such as Shock Top or Blue Moon.

“It’s the difference between ‘craft’ and ‘crafty,’” said Thompson.

A “Craft Brewer,” as defined by the Brewer’s Association, “is small, independent, and traditional.” In order to be considered a craft brewer, both production and distribution must be limited. Small breweries swallowed into larger breweries, Walker said, are also no longer craft breweries; they are hybrids.

“A craft brewer to me is someone who is fully enveloped in the business from soil to glass,” Walker said.

Walker, the lion on the logo of Firestone Walker Co., is one half of the duo that founded the craft brewery located in Paso Robles and Buellton, Calif. His brother-in-law, Adam Firestone, is the other half, and the bear on the logo.

“I was enchanted by the dirt to glass process,” he said. Firestone and Walker continued to grow their business in California, where there was a fairly even playing field for “small brewers to be born, develop, and survive.”

“[It was] a riddle of being an independent brewer in a monolithic world,” Walker said, further elaborating on the maze of being a small craft brewer in a beer market dominated by big names.

Thompson, brewer from Telegraph Brewing Co., spoke about the influence of California on his craft brew. He explained that he developed a passion for Belgian beers, sour beers, and barrel aged beers when he was home brewing.

“Lambics from Belgium got me really excited,” he said about the style of beer produced by spontaneous fermentation.

“When I decided to start my own brewery, I wanted to combine that sort of brewing tradition with the tradition that’s been developing in California for years,” Thompson said. “Bring the creativity of Belgian brewing here with all the wealth of what’s available in California.”

On the other side of the equation is Zach Rosen, a Santa Barbara beer connoisseur and member of the cicerone program. He is responsible for tasting and evaluating the craft brews that these brewers, among others, produce.

“I wasn’t the biggest fan of the physical part of brewing,” he said. “I’m a sensory analyst; it’s a wild card in the background [of brewing] that I became fascinated with.”

His analysis often includes how the environment influences perception, and he claims that California is the “ultimate place to experience that.”

While craft brewers currently only take up about 8 percent of the beer market, the industry has been growing since the 1980s, and more and more craft breweries are popping up around the United States–maybe even to the point where the craft brew market is getting just a little bit crowded.

“It’s getting crowded in the IPA market, definitely,” Thompson said, referring to the India Pale Ale style of beer. “I would like to see more breweries focusing on differentiation.”

“I think [new craft brewers] should learn to differentiate themselves just by their quality,” Rosen said, emphasizing quality control in addition to branching out.

To round out the discussion, the panelists each chose their “desert island beer,” or the brew they would want to have with them if they were trapped on a desert island for a month.

“Orval,” Rosen said, which is a Trappist ale brewed in Belgium. He explained that the brettanomyces, a special yeast, would cause the beer to never taste the same twice. “At least it wouldn’t be boring.”

Thompson went with a “good Czech pilsner,” a type of pale lager. “And it has to be fresh.”

Lastly, Walker went with a Sierra Nevada Pale Ale.

“I got completely romanced by west coast hops and the west coast craft beer story,” he said, a story to which he, along with Thompson and Rosen, have certainly contributed a verse or two.

Comments are closed.