Emma Boorman

Staff Writer

Photo by Benjamin Hurst

Typically, watching a ballet comes with the expectation of seeing a story. The most well-known ballets, such as “Swan Lake” and “The Nutcracker,” follow a clear sequence of events in spite of the lack of dialogue. This ability to tell a story through dance and music alone is already remarkable. Even more impressive is the potential of a dance to communicate ideas, emotions, connections between people, and anything else an audience can interpret during a two hour performance.

On Oct. 2, the American contemporary ballet company, Alonzo King LINES Ballet, performed at Santa Barbara’s Granada Theatre and demonstrated instead, the transformative potential of dance.Rather than telling a story, the dancers in King’s company interacted with each other, the music, the set, and the audience in a way that transcended storytelling, speaking to the individual souls of audience members.

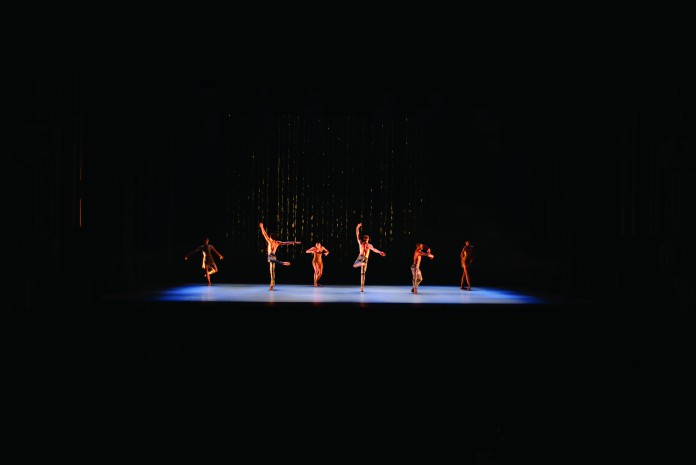

Set in a dark space, the first piece, “Meyer,” seemed all at once to balance the elements of natural and other-worldly, adding to the mystery and ambiguity of a performance that lacked a linear plot. The dark clouds and glowing rain in the background suggested the dancers existed in a world with some kind of plausible natural cycle, while the movements and music created a distance between reality and the show. The energy of the performers fluctuated, eliciting a wide range of responses from the audience. Certain actions of the dancers, the way one would fall, drag another one across the stage, toss and lick pieces of paper, or bathe in the shining rain would make people laugh, cheer, and quietly gasp simultaneously. The wild gestures and evocative music allowed the audience to witness physical and emotional connections that ordinary experiences cannot offer.

The second piece, “Resin,” introduced more interactive elements for the dancers to work with on stage. The dancers bathed in what looked like streams of shining sand, leaving residue to be kicked up and slid on throughout the rest of the performance.The added lyrics and spoken word also created an increased sense of purpose in the second half of the show, although that purpose is still ambiguous. The words were captivating, but the music, which King cited as “from the Jewish diaspora all over the world,” made it difficult to understand yet aurally pleasing. Like the first piece, “Resin” offered no clear story but provoked a great amount of sensuality and emotion.

After the performance, King answered audience questions, many of which pertained to the meaning and purpose behind his show, a show that was left entirely open to the interpretation of each viewer. His answers were not helpful to those seeking clear answers; instead, he told the audience that “everyone already knows what it’s about.” He elaborated, calling the show a “soul-to-soul greeting, heart-to-heart meeting.” For those who need to look for clarity in everything, this answer could be seen as unsatisfactory. However, the ballet’s lack of a clear message was a liberating and relaxing experience. King offered a performance that did not require a critical eye; it could simply be felt and enjoyed.

In the absence of clear meaning, the company visually and passionately portrayed what it feels like to be a human — more accurately than a plot-driven dance would have. King’s ballet demonstrated what it really means to be alive in a world where resolutions and purpose can be nonexistent.