Julian Moore

National Beat Reporter

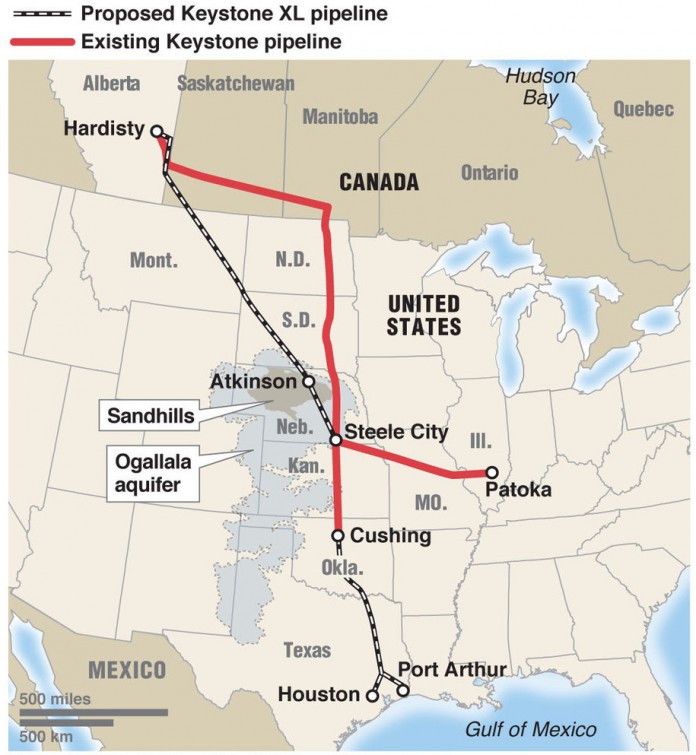

On Monday, the State Department moved one step closer toward its decision on whether it will build a controversial international pipeline between the United States and Canada. The State Department officially closed its period of public comment concerning the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, which would pump oil from tar sands in Canada to oil refineries throughout the Midwest if it is constructed. The pipeline, which was scheduled for construction in 2012, was put on hold by the Obama administration in late 2011 after protests by a host of environmental groups raised concerns over its potential environmental impact.

The debate over Keystone XL has proven to be one of the most public and polarizing of all the Obama Administration’s environmental policies. On the evening of Nov. 6, 2011, as many as 12,000 demonstrators, according to the Washington Post, descended upon the White House in a flash protest urging President Obama to halt his final approval of the project. The protest succeeded, and Obama ordered a review of the State Department’s environmental report that has yet to conclude.

But proponents of the project say that the 1,700-mile oil infrastructure project would create thousands of jobs during construction while also easing the United States’ dependence on oil from OPEC nations such as Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. TransCanada, the Canadian firm in charge of the pipeline’s potential construction, estimated in 2011 that the project would hire 20,000 Americans through 2012 and deliver 590,000 barrels of oil per day to the United States. Canada is currently the single largest exporter of oil to the United States, pumping over 2 million barrels of oil per day in American oil markets, according to the Washington Post.

Still, few places have shown greater opposition to the Keystone Pipeline than in states such as Oklahoma. In that state, where environmentalists have rarely been welcome before, citizens and politicians alike are expressing concern with the potential effects a leak in the pipeline could have on the treasured Ogallala Aquifer. The Aquifer supports an estimated $20 million in agriculture across the eight states of America’s “bread basket” along the pipeline’s path. Furthermore, environmental activists such as Bill McKibben have argued that bitumen, the type of oil extracted from the Canadian tar sands, is significantly harder to clean up than its alternatives.

Keystone XL has also met resistance from legal advocates who are opposed to TransCanada’s aggressive eminent domain claims to land along the construction path. According to the New York Times, by October of 2011, before the project met initial resistance from environmentalists, as many as 56 landowners in Texas and South Dakota had taken TransCanada to court, according to the New York Times. The plaintiffs in these cases have maintained that TransCanada has illegally sought to claim land in the United States owned by private citizens, including farmers, in order to complete construction. Eminent domain laws generally allow for the confiscation of private property if taking it is designed to serve a larger public good. The Texas Ninth District Court is currently reviewing whether or not the company is allowed to condemn land in the United States without a formal agreement in place with the United States.

Earlier this year in Washington, Santa Barbara representative Lois Capps proposed an amendment to a Congressional bill that would authorize the pipeline project. Capps’ amendment would explicitly make bitumen subject to an eight-cent-per-barrel tax, which sparked a debate that ended when committee Chairman Fred Upton (R-Mich.), promised to work to resolve the issue.

Photo courtesy of sites.psu.edu

Comments are closed.