Cheyenne Johnson

Staff Writer

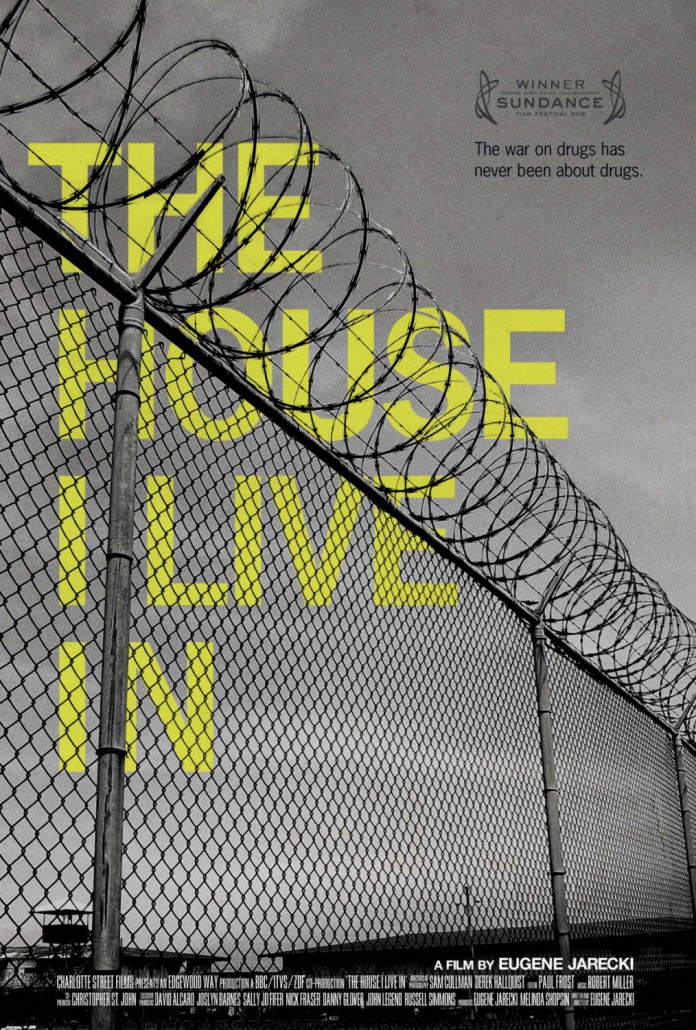

Photo courtesy of the UCSB Multicultural Center

The dire effect drugs have on people, as well as those who know them, demanded attention at the University of California, Santa Barbara’s Multicultural Center’s Feb. 6 screening of “The House I Live In,” a documentary film by Eugene Jarecki about the United States’ drug war and the costs it has on the country. The film moved from addicts to sellers, family members to narcotics officers, senators to federal judges, and inmates to wardens as it tried to gain a grasp on the scope of the war, and how it transitioned from one of rehabilitation and condolence to one of ostracism and hatred.

The film spanned over 20 states and combined stories of cocaine, crack, opium, and marijuana to provide a view on the varying influences that led to Nixon’s declaration of war on drugs in 1971. Jarecki revealed that though arrests and punishments have steadily increased from their original level, drug use has continued to increase, with the dream of eliminating drugs in America long since faded.

Prison guard Mike Carpenter stated in the film that though he supports the prison system, the flaws in current drug policyhave caused him to question the logic behind it.

“I think a long time ago, we made drugs into this huge thing, and we’ve made it so illegal, and we’ve made it such a national issue with that tough on crime stance,” said Carpenter. “I mean, you can’t get elected if you don’t profess to be tough on crime. You can’t stay elected if you don’t do things to be tough on crime. Nobody can afford to be the first guy to say, ‘Wait a minute. We can’t afford what we’re doing. Let’s do something different.’ Because if you even made a noise like you were going to be soft on crime in any way, you would be out of a job.”

The relationship between policemen and drug laws and users is a complicated one, according to Jarecki. Since the war on drugs began, over 45 million people have been arrested, a feat that’s made the United States the world’s largest jailer. Though the U.S. has only 5 percent of the world’s population, it holds 25 percent of the inmate population on the planet.

David Simon, a former police reporter as well as the creator, executive producer, and head writer for the HBO television series The Wire, said the way the country rewards its police force is a key contributor to the problem. Police officers are generally given overtime after a drug bust as they have to take the drugs to be processed, have to take the prisoner to central booking, and finish paperwork.

“He’s gonna do to 40, 50, 60 times a month so that his base pay might end up being only half of what he’s actually paid as a police officer,” said Simon. “We’re paying a guy for stats.”

Simon said the focus on non-violent drug users is severely distracting officers from more complicated and intricate cases that require more work and offer less financial reward.

“Compare that guy to the one guy doing police work,” said Simon, “solving a murder, a rape, a robbery, a burglary. If he gets lucky, he gets one arrest for the month…And at the end of the month when they look and they see Officer A, he made sixty arrests. Officer B made one arrest. Who do you think they make the Sergeant?”

Jarecki goes on to show that not all drug laws are created equal and claims that, for all the nation’s talk of protecting the population from the dangers of drugs, that may not be the true reason for the current punishments and regulations. Jarecki argues that opium laws were implemented in California to stop the influence of immigrant Chinese workers, crack cocaine laws to attack African Americans in urban areas, and marijuana laws to affect Mexican workers along the border.

Overall, Jarecki’s film took a glance at every aspect of the drug war. He scanned across states and decades to show that where the U.S. has arrived was not as a result of a steady or clear cut path. He noted that people serve life sentences for dime-sized amounts of meth, families fall into cycles they can’t seem to escape from, and inmates are expected to leave jail rehabilitated despite no rehabilitation services being offered. The film reveals that there is nothing black and white about the drug war, and to approach it simply is irresponsible.

Poster Courtesy of Charlotte Street Films

Comments are closed.