Deanna Kim

Staff Writer

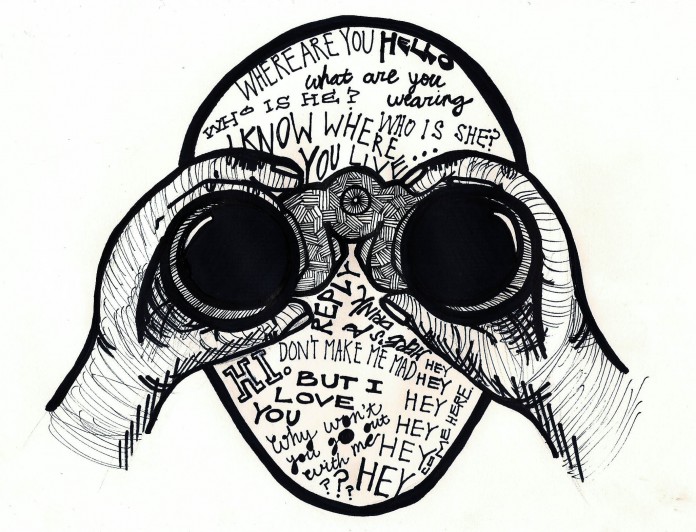

Illustration by Deanna Kim

Getting to know someone without actually talking to them is something quite common in today’s era. With social media networks such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, someone’s public life can be viewable a click away. I would be lying if I said that I have never searched someone’s name on Google or tried to find my crush’s Facebook account. But with this available information so readily attainable at our fingertips, the term “stalker” has been blurred. Am I a stalker for looking through a stranger’s photos on Instagram and knowing they ate a burrito on a Thursday night?

The term “stalker” is now used casually, like an adjective, usually accompanied by the words “creepy,” “obsessed,” and “weird.” It no longer only means a person who pursues and harasses a person without their consent or knowledge. It is a term thrown around by people who were shown interest by someone considered undesirable socially or physically, and a term used as a means of maintaining one’s status and desirability as “superior.” Just because you see the same guy or girl every Tuesday on your way to Campbell Hall doesn’t mean they’re following you—they probably have class in that area at that time. Now, if they follow you to bathroom, that might be a different story. But still—we give ourselves too much credit for thinking everyone is “obsessed with me.”

However, as loosely as the term is used, stalking is a serious problem. According to victomsofcrime.org, 6.6 million people are stalked in one year in the United States, 11 percent are stalked for five years or more, and weapons are used to harm or threaten the victim one out of five cases. The National Center for Victims of Crime defines stalking as, “a course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to feel fear.” This fear is not fear perpetuated because of a person’s conceit or narcissism, but the fear for one’s safety and existence—especially after it was clearly verbalized and expressed that this attention and interaction is undesired and nonconsensual. Thanks to TV shows and movies, measures to reduce a stalker’s ability restraining orders are made funny, desensitizing us from a very real issue.

It is natural to act curious regarding someone of interest, like a future roommate, co-workers or friends, and these social medias are an easily accessible form of doing so. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to see your ex-roommate’s Facebook album of Coachella 2012. Many of these sites are meant for others to publicly view, so that others can get a sense of that person’s personality and life; however, when the sites or knowledge obtained is used to harm the victim, is constantly monitored, and used for harassment, curiosity turns into stalking.

So please, if you find yourself becoming obsessed and absorbed in knowing a specific person’s or groups’ whereabouts, what they are wearing, what their next meal is, their favorite color, deodorant scent, and daily life—stop. It is neither healthy for you nor the victim.

Especially in a young college town, it is easy to confuse someone’s response that they are not interested as “playing hard to get.” In the right circumstance, they might be playing hard to get, but after a certain point, not interested means not interested, and it is time to move on. And not move on as in to the next victim, but to move on in life.