Kyla Woods

Contributing Writer

UC Santa Barbara’s Art, Design, and Architecture (AD&D) Museum opened two exhibitions from Jan. 18 to April 27: “Tomiyama Taeko: A Tale of Sea Wanderers” and “Public Texts: A Californian Visual Language.” These exhibitions, although separate, interweave similar cultural themes of the artists involved.

“Tomiyama Taeko: A Tale of Sea Wanderers” features the works of the late Japanese artist Tomiyama Taeko, who used oil paintings and mixed-media collages as a storytelling device to unravel the complexities surrounding her Japanese ancestry. Taeko’s works mostly deal with analyzing Japan’s imperialism through the lens of feminism. In her artwork, she criticizes Japan’s violent imperialism throughout the 20th century, paying particular attention to how people under imperialistic systems exist within it. Taeko grew up in Japanese-occupied land, and she uses her art in order to not only explore this part of herself but also shed light on this unfortunate aspect of Japanese history.

Taeko relates the imperialistic wars of Japan in the 20th century to contemporary conflicts. In her piece “In Toxic Seas,” she depicts 9/11, keyboards, and oil fields to comment on American imperialism. In an interview with Eleanor Rubin, she says, “So the beginning of my career as an artist was marked by the Manchurian Incident, and now at the end of my life, we have another war, the one that started with 9/11.” In many of her art pieces, she asks the question: what do people learn from history?

Her paintings mostly depict puppets and puppeteers across different Asian cultures. One of these paintings is the piece “Wandering Minstrels and Puppeteers.” In this painting the puppets are inspired by Malaysian, Indonesian, and Chinese culture. She calls the characters depicted troubadours, travellers who showcase their culture around the world. The frequency of puppets and puppeteers within Taeko’s work represents Taeko’s interpretations of traditional culture; she implements these images within her art to tell stories surrounding her personal experiences surrounding imperialism.

“Public Texts: A Californian Visual Language,” features multiple Californian artists. These works are a representation of not only the artist(s) who made it but of Californian culture. All the works within the exhibition are composed of multiple artistic mediums, each respective to the story told within the piece.

Many of the artwork references Californian motifs, such as “Injured?: I,” by Alfonso Gonzalez Jr., which depicts graffiti and prominent California insurance companies from L.A. Even though graffiti and insurance companies may seem mundane, these motifs are prominent enough in L.A. to be a significant, relatable aspect of California culture.

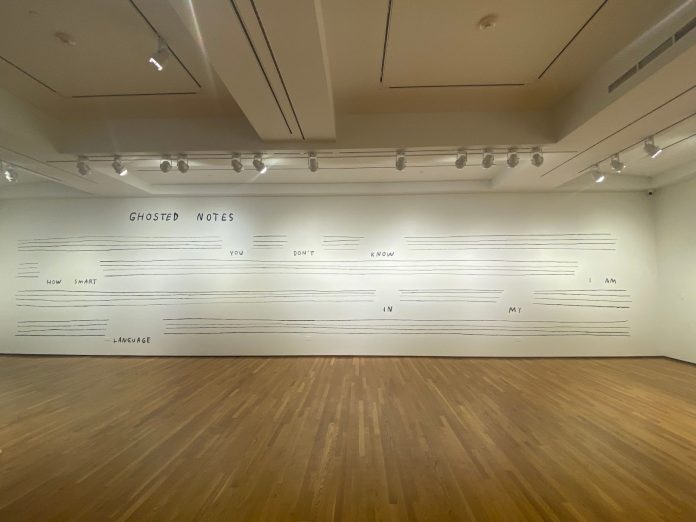

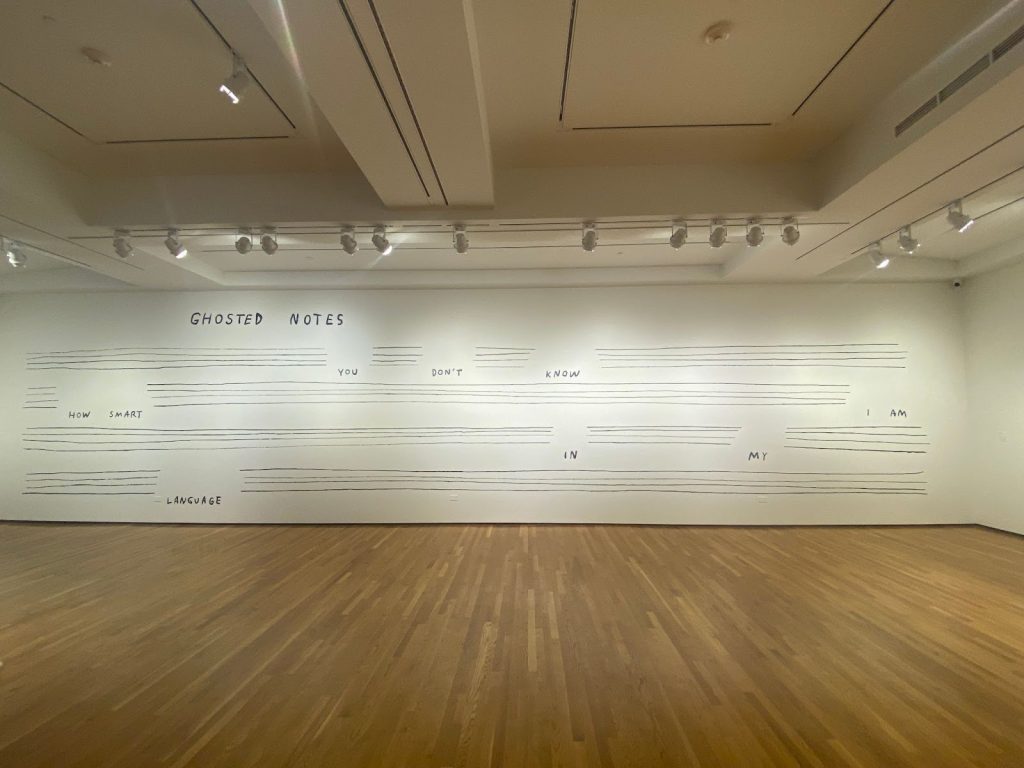

The exhibit doesn’t just focus on what represents California as a whole; it also pays attention to the individual experience of a Californian. The mural piece “Ghosted Notes (You Don’t Know How Smart I Am in my Language),” by Christine Sun Kim, deals with Kim’s experience growing up as a deaf person using sign language. Her piece analyzes how language barriers can often separate us and hinder mutual understanding. She relates this to the many languages spoken within California, such as indigenous languages.

Tomiyama Taeko and the artists contributing to “Public Texts: A Californian Visual Language” base much of their art within their culture. Sometimes, the use of cultural art can be a form of criticism or protest, like Taeko’s or Kim’s art, or it may showcase a shared culture, like Gonzalez’s art. This exhibition is an example of how visual art can tell a lot about how people grew up with different influences. Learning about each other’s backgrounds is crucial, especially in these times. Even though art may seem frivolous, it is crucial to how we improve and criticize our world. I encourage people to visit these two exhibitions and analyze the stories that these artists tell.