Camila Martinez-Granata

Opinions Editor

Language (noun): a body of words and the systems for their use common to a people who are of the same community or nation, the same geographical region, or the same cultural traditions.

This is but a mere ambiguous definition of language and whom it applies to. Yes, this definition is from the dictionary. No, I don’t agree with it.

From the naive age of five, every individual in America is sent to school, with the purpose to gain knowledge in math, science, literature and so on. The great odyssey of our education in the 21st century continues until we reach our undergraduate career in college—often times we choose to venture beyond that. Along the way, we are taught a particular set of grammar rules, speech structures and vocabulary that is socially acceptable.

The truth is, our language and the way we speak is molded and controlled by how advisers of education and manufacturers of textbook companies want individuals to speak, write and think. The assumption that if you teach a person how to compose all aspects of expressing themselves in a cold, structured manner will make them a better citizen is a fallacy. It’s conformity. Not individuality.

I can compromise on the fact that in elementary and middle schools the structure of the English language is impertinent to increasing the intelligence and improvement of future generations. It’s obvious—language is how we communicate.

But there is no way that a school’s curriculum can capture the unground dialects and slangs that exist in every community. I remember the first time I heard the f-word: I asked my teacher what it meant—and aside from sending me to the principal’s office, she didn’t even answer my question. It’s undeniable that aside from our academic careers, as children we are exposed to swear words, slang and other terms that we don’t learn in school.

There is a widespread fear that if we allow our youth to know terms we give a negative connotation to, they’ll sound “stupid.” Just because I use the word “hella” or “hyphy” doesn’t mean that I’m not going to pass the 11th grade or not score a 5 on an English Advanced Placement test.

By the time I left high school, I already had a sense of my own style of writing and speaking—regardless of the suggestions from teachers to improve my style. It isn’t a matter of sounding educated or smarter than someone—people equate diction with intelligence. It’s a misconception we’ve been taught since that very young age of five, and it’s created unfair stereotypes and restrictions in self-expression.

How can you prove this assumption wrong? Take a look at the versatile body of students we have at University of California Santa Barbara. There are people of all walks of life—from different cities, states and countries with different economic statuses. You have all been accepted into this university because you were academically qualified to be here. Everyone at UCSB is united by this common thread—and everyone here has the freedom to speak, think and write how they want.

Spoken word, media organizations and groups like Laughology remind us that while we might not be able to use certain vernacular in a term paper, we can still express our lives, thoughts and emotions as we please. Is it because we’re at college and young adults? Maybe.

In an ironic way, the years of sitting in an English class and having to distinguish a gerund from a predicate has paid off. Not because people can be accepted into colleges—but because the only thing left to do with our language is to manipulate it.

We can create new meanings by putting two words together. Instead of writing about an event, we can describe and stimulate the details and feelings under which that event occurred. You can experience what it was like to feel, see or be part of something—with the simple use of words.

Language is an art. You have to learn to hold a paintbrush before you can paint. And from there, your possibilities are endless.

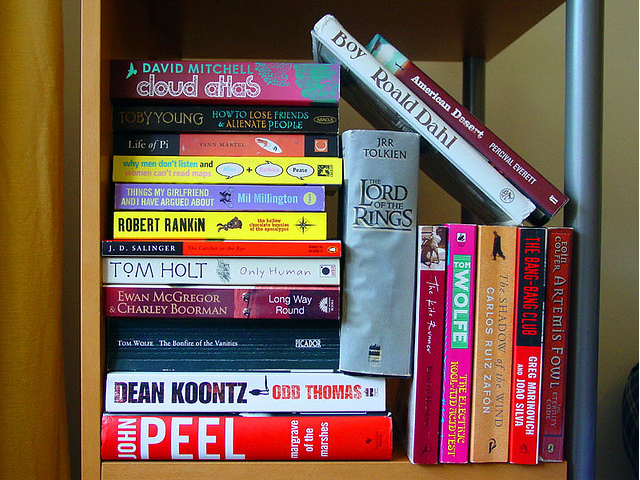

Photo Courtesy of Ian Wilson