Matthew Brooks

Staff Writer

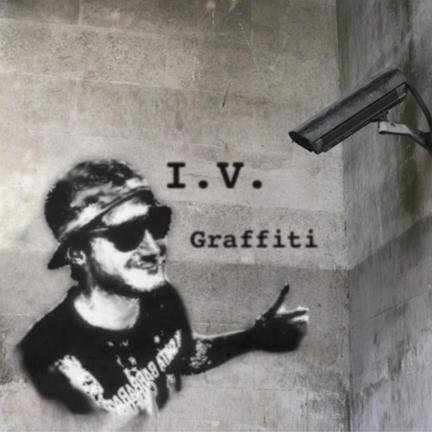

Photo By: Matthew Brooks

Just around 2:00 a.m., on the outskirts of Isla Vista, I approached the tomb-like remains of what is rumored to be an abandoned jailhouse at the base of the beach cliffs. In reality, it was once a beach house, but over the years it has become a dilapidated shrine to the graffiti that covers every inch of it. Sliding down a steep path brought me to the top of the tallest wall that was fixed into the cliff. Below me, I saw three shady figures. One of them loomed around with a can of aerosol spray-paint and was tagging a wall while the other two looked on. This was just the sort of scene I’d hoped to find.

Their eyes all shot to me as soon as I spoke. I felt like I’d just sounded the seventh trumpet of the apocalypse by intensity of their stares. I was scared, but in a way, things were going better than I expected: they hadn’t fled and I hadn’t been jumped.

I was just about to explain myself when, as if I never mattered at all, the artist went back to work. His two buddies lounged against a wall and one of them called out to me saying, “Waddup? You here to hit up this place too?”

I was invited to stay, but I could tell the artist didn’t like me being there at all. He was nervous and refused to say much. I watched as a silver and purple “throw-up” emerged in the wake of his can. A throw-up is like a tag, but while any carelessly sprayed name or nickname qualifies as a tag, throw-ups usually consist of bubble letters with outlines. I thought of the photos taken of this place that I’d seen on display in UC Santa Barbara’s Davidson Library. They were what first made me see graffiti as something beyond the territorial piss-marks of inner-city gangbangers or the mindlessly scribbled penises found in bathroom stalls. In those pictures (donated by a now-retired UCSB professor named Michael Arntz) I saw fantastic, vibrant artwork that transformed walls into canvases on which messes of color clashed together unintentionally to form collective designs.

Various forms of graffiti can be found throughout history. According to Pamela Dennant, a graduate student at Thames Valley University, modern graffiti was born in New York City during the late 1960’s. Kids who spent their days hanging out on the concrete stoops of poor neighborhoods pioneered it. While daytime was ruled by walking suits, nighttime was theirs. They found purpose in inscribing their names on the very lifeline of urban society: the subways— those high-speed steel serpents that the out-of-touch lords of the modern day Babylon filed into every day.

Nikki Leone, a UCSB Art graduate student, gave us her definition of the spray painted walls and buildings of the world.

“Graffiti is Street Art. Most people have the wrong impression of what actually constitutes work to be ‘graffiti.’ Anything that is marked on a public surface is technically graffiti. Not just burners, throwups,tags, and puppets which people usually associate the term graffiti. Street Art does not become Graffiti. It is Graffiti,” she said.

The walls of the beach shack had evolved since the library photos were taken. It was an entirely different site on which new artists had come and left their marks: where there was once a moon with a face, there was now a massive Wolf bearing symbols of Mexican American pride.

I thought of how graffiti artist Coda once said that to graffiti is “to pour your soul onto a wall and be able to step back and see your fears, your hopes, your dreams, your weaknesses, really give you a deeper understanding of yourself and your own mental state.”

When I asked the artist I met on the beach why he was doing graffiti, his friend answered for him saying, “I don’t think he knows. We’re just here chillin’. He [the artist] just does this for the hell of it. I play the drums; he does this.”

All this time I thought I had an idea of what graffiti artists were about. I was hoping to find the “prophets” who write on “subway walls and tenement halls” that Simon and Garfunkel sang about in the song “Sounds of Silence.” I imagined these were artists eager to make their presence felt in a world that is too big and busy to otherwise notice— but felt like I’d just stumbled on a kid diddling with a “hobby.”

Frustrated, I asked a graffiti enthusiast friend of mine to point me in the direction of a more well-known artist. He told me about Banksy, who is one of the most popular current artists. Banksy’s satirical stencil graffiti has been appearing on buildings and objects all over the world since the early 1990’s and I liked his work, at first. Then I found out that this supposedly anti-consumerist artist once sold his work for around two million dollars to Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie. If that isn’t hypocrisy, I don’t know what is.

Artist Tim Rollins once said, “It is difficult to accept [graffiti] on white gallery walls. Then it becomes part of the commodity market. The social context is what gives it meaning and this is being ripped from it.”

At the same time, I realized Isla Vista is a town full of emerging educated, well-to-do alcoholics. Its student populace is among the cream of the crop of this country and is far from being comparable to the rebels who pioneered graffiti in the 1960’s. And Isla Vista’s graffiti accurately reflects that. A lot of it has a nonchalant style and a sense of humor, like the playfully self-aware phrase “non-¢” that has become a popular site around town or the stickers featuring Hank Hill’s face from King of the Hill that can be found stuck on everything from lecture hall chairs to street signs.

The local artist I met deserves our respect. He, along with other local graffiti artists, have given that old shack on Devereux Beach new life as an ever-developing extension of Isla Vista’s fun-loving and creatively unique spirit.