Kelly Depner

Writer

As the upcoming midterm elections approach, Californians have been inundated with advertisements, news media, and political pundits focusing on the gubernatorial race. Gossip and speculation abound about which party will obtain control of Congress: will the Democrats retain their majority or will Republicans take over both Houses in an upset reminiscent of the 1994 elections?

Amid the partisan prattle, local nonpartisan elections have been drowned out, garnering little to no coverage. But while these elections may not have national repercussions, for local residents their impacts are more consequential and sometimes they are also more interesting.

For Santa Barbara residents, the election of four members to the Community College District Governing Board is rife with controversy and anti-incumbent fervor. Four incumbent Board of Trustees members are currently being challenged in the upcoming November 2 election, a feat that hasn’t occurred since 1965.

Combined, these four members have served on the Board for a total of 104 years with Kathryn Alexander serving the longest amount of time: 45 years. With such an ensconced stance, the question is, why are they being challenged now?

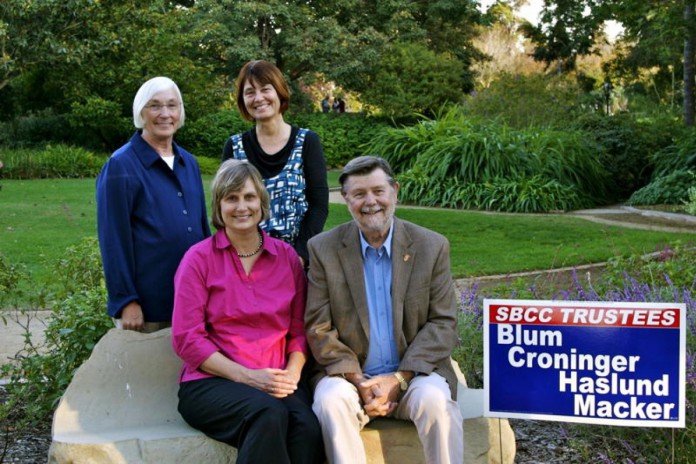

In a truly grassroots movement, four SBCC supporters have teamed up to run together to replace the four incumbents seeking reelection. Marty Blum, Marsha Croninger, Peter Haslund, and Lisa Macker, all familiar faces in the SBCC community, were drafted to run for the Board by the very citizens they seek to represent.

Marty Blum may be most familiar as Santa Barbara’s former mayor. Her decision to run for the Board was prompted by an incident during an advisory board meeting for Adult Education. A group of members wanted to raise money for the college in an attempt to save classes scheduled for cancellation in the summer session.

To Blum’s surprise, President Andreea Serban dismissed the idea, saying that it was illegal. When pressed, Serban added that even if it were legal, it would require hiring a bookkeeper and other administrative hassles. Blum was struck by the comments and decided to do her own fact checking. What she discovered were a list of complaints from various members of the community involved in the Board of Trustees jurisdiction.

Marsha Croninger, who has been an environmental attorney for over 30 years and has worked in California’s government for eleven, investigated further. She describes her findings as a lack of “shared governance,” such as obtaining input from faculty and students on decisions affecting them before the decisions are made.

Under the law, the Board is required to allow citizens access to public records of their meetings.

“Citizens who could not attend Board meetings wanted to know what happened,” Croninger said.

“The minutes did not tell the full story and some complained they were inaccurate.”

As Blum puts it, the Board is being “pennywise but pound foolish.” Their cutbacks have had a devastating effect on many people, yet cutting summer classes has only saved an estimated $500,000 or less, a mere pittance compared to the total budget.

Croninger complains that the college has also failed to disclose the amount of cuts they’ve made. She discovered a bilingual computer class was shortened from 13 weeks to ten weeks, which the college did not disclose as one of the programs cut in its list of classes to be cut or reduced.

But the real problem the four have with the Board, expressed to them from various members of the community, is the lack of process and community involvement. The four describe the process involved in decisions as simply “rubber stamping solutions [President Serban] brings to the meeting” which usually consist of cutting classes and that “the only thing left to discuss are which classes to cut.”

If elected, the four propose several solutions to the problems they’ve identified. For starters, they plan on slowing down the decision making process and, most importantly, involving faculty, students, and the community. As a faculty member at SBCC for 40 years, Peter Haslund described education and community college as “the great leveler” of people from all socioeconomic groups.

The four point out that the current Board continues to cut classes and lay off teachers as a default, suggesting a complete disconnect with the SBCC students and faculty. If elected, Haslund will be the first long-term faculty member to serve on the Board.

All four recognize the importance of saving classes and faculty members’ jobs. They look at education in terms of what is needed for future job markets. As such, they want to increase classes, and in some cases create classes, which are designed to prepare students for careers in green jobs, sustainability, and an increasingly connected world.

In Fall 2009, 1,871 transfer students enrolled at UCSB, 9 percent of the total undergraduate population and almost 30 percent of all new undergrads. Most of these students have been directly impacted by the community college system. While not all UCSB students have personally attended community college, all are part of the sphere of public education, and with increasing cut backs and increased fees, all understand the trials and tribulations of fewer classes, smaller class sizes, shortened class periods, and fewer teaching assistants.