Brian Gallagher

Staff Writer

It takes a special breed of depravity and charm to be a Jack Unterweger.

Before his neck hung from a self-strung shoelace noose in an Austrian prison cell in 1994, this spirited womanizer murdered over ten prostitutes, a few of which he managed to off while masquerading as a journalist reporting on Los Angeles city prostitution.

To bring this enigmatic figure back to life—that, it seems, can only be done by a breed of one.

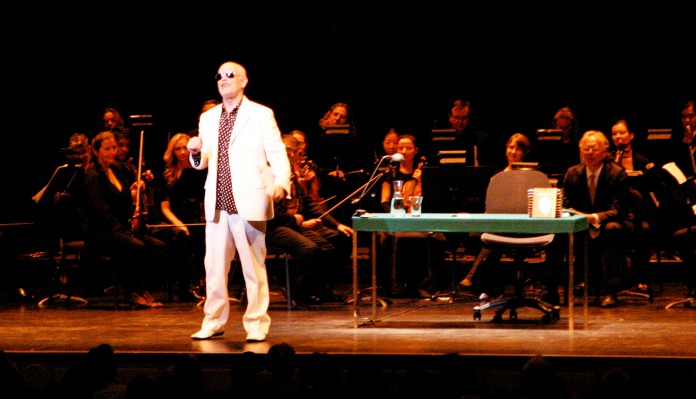

John Malkovich, being the superbly seasoned and illustrious Hollywood actor that he is, dons Unterweger’s sinister persona with a disturbing authenticity. Shown for just one premiere event at Santa Barbara’s Granada Theatre, “The Infernal Comedy: Confessions of a Serial Killer,” darkly and wittily spins humor out of horror, and leaves you tainted with sympathy for a villain who just seems like an uncannily likable guy.

The play’s director Michael Sturminger, who has gained most of his experience writing and directing documentaries, is relatively new to stage-performance. His take on “The Infernal Comedy” can bee seen as a kind of mockumentary of Unterweger’s life—he wrote, and killed prostitutes, so now Sturminger takes it a step further, combining the two. He has the murderer offering a written collection of novels about his life killing prostitutes for sale. (That’s any publisher’s dream, right?)

In the play’s opening moments, its baroque ensemble conducted by Martin Haselböck, Musica Angelica, stirs to life while Jack Unterweger saunters in from stage left, arms lifted to warm applause, adorned in a suit pristinely white. On the stage sits an office chair and a fold-up table, atop which rests a stack of books on display, all entitled “The Infernal Comedy”. Unterweger is here on a book tour, and he’s eager to let loose about all of his blood-spilled thrills and women he’s killed over the course of his peculiar and unfortunate career.

Told partly through his own brashly sincere monologue, and partly through the arias of two lovely female sopranos, the story of Unterweger begins with his childhood desertion by his parents. His Viennese mother and his American soldier father send Jack off to his alcoholic grandfather to provide some semblance of a home. He becomes a troubled youth, assaulting prostitutes here and there, frequenting prisons, until he lethally strangles a hooker for the first time with her own bra.

Fifteen years to parole, left only with the comfort of his thoughts, Unterweger churns his memories into short stories, poems, and plays, forging himself into a minor Austrian celebrity, of which he does not tire of boasting.

To chronicle the tragedies experienced among Unterweger’s victims, two sopranos sing spectacularly moving arias, which reveals their angst and their woes, their pity and their shame at having been stripped of all dignity in death. Not only do these ladies display their astounding vocal range and depth, as well as dramatically sustain peak spintos, they perform under duress of Unterweger’s harassing forwardness and sexual advances. These come playfully at first, becoming progressively more grave until Unterweger no longer desires their company, nor that they keep living.

The criminal’s cocky zeal and measured assertiveness have an impossibly captivating charm that punctuates each and every one of his sentences. Malkovich skillfully assumes Unterweger’s characteristically sinister poise and unfailing gumption. His is almost an anti-performance: Malkovich-as-Unterweger speaks to the crowd with such flowing ease and with such unreal sincerity, on topics so familiar and close to the heart, that it seems he has ceased performing and is speaking as himself.

“When was the last time,” asked Malkovich to an elderly woman near the front row, “you enjoyed making love?”

The audience broke into an eerie laughter. It felt like it wasn’t Malkovich that was asking, it was Unterweger himself—Unterweger the murderer, the rapist, the miscreant. The woman was communicating with a person that kills people, yet it all felt so weirdly cheery. The way Malkovich carried himself, the way he spoke, made Unterweger’s murderous hobby seem just like that.

Given a computer to access the internet, Unterweger reacted most unexpectedly with the technological quip, “A fucking Mac?” To the audience he cried, “Let it be known, Jack Unterweger is a PC!” Malkovich possesses coolness in his sway and a swagger in his cadence that has a disarming way of humanizing the inhumane.

Malcovich does an astounding job showing that Unterweger clearly does not regret the person he has become. He’d do it all over again given the same choice. An oddly fascinating infatuation with fate exudes through the unwavering perspective of integrity he sees in his life throughout the play.

“Could I be anyone else?” he wonders aloud. “No, all else is boring.”

Comments are closed.