Troy Sambajon

National Beat Reporter

Many people may not know this, but Santa Barbara once had a thriving Chinatown and Japantown, or nihonmachi, right off State Street. During this time, more than 900 Chinese and Japanese immigrants and their families settled down in downtown Santa Barbara. But when natural disasters and World War 2 internment struck, their livelihoods became vulnerable. Their homes were gentrified and the city paved over their history. Now, the only thing left of Santa Barbara’s Chinatown and Japantown are two plaques on Canon Perdido Street. For this Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) Month, The Bottom Line revisited the city’s archives to recover the stories of these Asian American communities and what caused the loss of their history.

The 800 block of Anacapa Street and the 100 block of East Canon Perdido Street housed Santa Barbara’s first Asian immigrant communities. The first Chinese immigrants arrived in Santa Barbara in the 1860s, working in abalone fishing, farming, laundry enterprises, and domestic service.

In a time where Chinese immigrants were not welcome in America, Santa Barbara was very open and welcoming. Children of Chinese immigrants were allowed to attend integrated public schools, instead of being segregated like others in the majority of the country.

In 1890, the Chinese community grew to make up 10 percent of Santa Barbara’s population. At this time, the first generation of Japanese immigrants, the Issei, began to immigrate to Santa Barbara.

Chinese and Japanese immigrants built a home for themselves along Anacapa and East Canon Perdido Street. The 1910 census reported that over 200 Japanese people lived in Santa Barbara; by 1940 there were over 500.

In these communities, Chinese and Japanese immigrants built small businesses, churches, hotels, and even local baseball leagues. Santa Barbara’s Japantown, or Nihonmachi, had many businesses catering towards Nikkei immigrants and non-Nikkei clientele, like flower shops, restaurants, barbershops, bathhouses, and markets. The Japanese Buddhist Church and Congregational Church, built in 1913 and 1916, played an important role in community networking and coordinating social activities, such as bilingual language classes, judo classes, and screenings of Japanese movies. A group of young Japanese Americans from the Buddhist church also formed a baseball league and hosted popular regional teams for locals to enjoy.

But, these Asian communities soon fell victim to natural disaster and neighborhood gentrification.

On June 29, 1925, Santa Barbara was rocked by a 6.3 Richter scale earthquake, demolishing 85 percent of the commercial buildings downtown. Over the next decade, the city of Santa Barbara would rebuilt a new Santa Barbara with the headline, “Spanish Architecture to Rise from Ruins.” Under this reimagining of the commercial district, prominent local property owners dismantled old Chinatown in the attempt to create a cohesive “Spanish colonial revival’”look for the city.

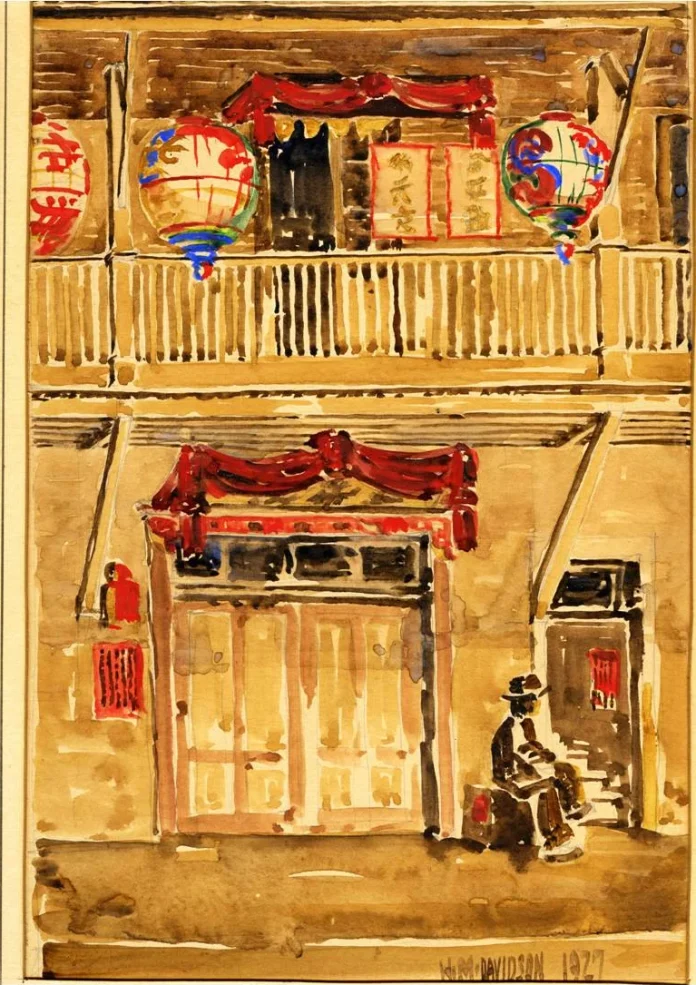

In response to this gentrification, a local real estate owner built a series of structures one block away to encourage the dwindling Chinese population to remain downtown. By 1930, the remaining residents of the old Chinatown had moved to this New Chinatown. Not long after, more areas of Nihonmachi were also lost, when a new Spanish colonial-style U.S. Post Office replaced Japanese businesses on Anacapa Street, which still stands today.

Beginning in 1942, thousands of Japanese living in the United States were forced to relocate to internment camps throughout the West coast. After the war, some of the incarcerated returned to Santa Barbara, but many could not.

In face of the fracturing of its community, the Japanese Buddhist Church and Asakura Hotel served as hostels for those who returned from the internment camps.

By the late 1950s, the Japanese and Chinese communities had lost many families and property. Within the following years, the Asakura Hotel, the Buddhist Church, and the Congregational Church were all destroyed.

On the land where Buddhist and Congregational churches once stood, the Presidio was reconstructed to solidify the re-envisioning of Santa Barbara. Where the Asakura Hotel hosted hundreds of young Japanese immigrants, the land was paved over to become a parking lot. You can still visit that parking lot today, and if you were to visit, the only visible remnant of Santa Barbara’s first Asian communities is a plaque on the wall of the last structure of New Chinatown from 1947 and a plaque in the Presidio lot.

From immigration to internment and replacement, history has left the Santa Barbara AAPI community looking for their yesterday, before their history might once again be paved over and forgotten. This history tells of how Chinatown and Japantown were demolished and almost forgotten because they didn’t fit with the reimagining of downtown Santa Barbara. These vulnerable communities became targets and their homes were gentrified to fit a better, cleaner narrative for Santa Barbara’s aesthetic and identity.

In the mid-1800s, immigration brought thousands to California and a few hundred Asian immigrants coming to Santa Barbara. Their communities are not completely forgotten — in fact, the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation has worked extensively to document the diverse history of the people who lived here. However, it’s hard to erase the fact that these people, their lives and their history, were forgotten, paved over and replaced. All that’s left of their once thriving communities are now, simply, plaques on a wall.

To learn more about the history of Santa Barbara, visit the Nihonmachi Revisited Exhibit at El Presidio de Santa Bárbara State Historic Park and visit the archives at the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation.