Han Do

AS Beat Reporter

If you walk into any college lecture hall and you will undoubtedly see rows upon rows of opened laptops, the sounds of students diligently typing away permeating the room. But upon taking a closer look, many students are either shopping for boots, checking emails, or doing some other unrelated task.

Trung Bui, a third-year computer science student at UC Santa Barbara (UCSB), said that when his professors go on a tangent and talk about something unrelated, he often feels tempted to use this time to do something else.

“[The professors] always preface it with ‘this is not going to be on the exam,’” Bui said, making it even more tempting to want to zone out.

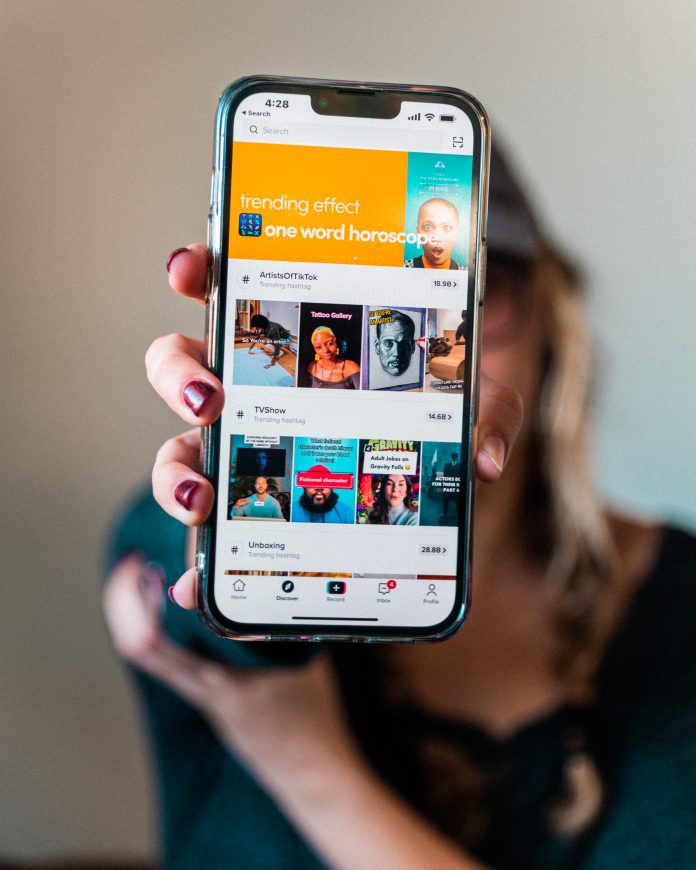

Multitasking and social media addiction have been said to impair focus and decrease performance. With COVID-19 and social distancing, technology became the only way to navigate school, work, and social relationships. As life returns to normal, many students still struggle with finding focus and defining their relationship with technology.

Many multitask while they are in class by checking social media. “I would tell myself ‘five more minutes,’ which turns to 15, sometimes 20 minutes,” Bui said.

When he manages to go off of social media for one or two days, Bui said it makes him feel a strong sense of FOMO (fear of missing out), despite knowing that probably nothing too important is going to happen.

Bui admits that multitasking has been the opposite of beneficial for him, because every time he switches tasks, for example, between listening to lectures and checking emails, it takes a while before he is able to “get back into the groove” and refocus his attention on learning again.

But at this point, multitasking and scrolling on social media has become a habit that is hard to break.

Bryan Zamora, a third-year computer science student, said that at the beginning of the pandemic he noticed his screen time drastically increased. With so many things going on in the world at the time, he found himself constantly checking the news and scrolling on social media.

The turning point for Zamora was when he watched the documentary “The Social Dilemma” on Netflix. “It made me realize the reason why I’m on my phone so much is because these algorithms were created to make us addicted,” Zamora said.

According to Dr. Ronald Rice, a communication professor at UCSB, whose research focus is the diffusion of innovation and technology, people have always had the same hope and concerns regarding new technologies. We think about social media nowadays the way people thought about television when it first came out, for example, that it’s going to completely tear apart our social fabric.

What makes social media different, Rice said, is that it embeds you in a very rich social network — you are no longer simply an individual user.

“Most people [now] feel a responsibility to respond to others. You feel driven to find out what other people are doing,” Rice said. This process often involves constantly monitoring your presence and the social groups you belong to.

In addition to having a strong social component, excessive social media use also has a behavioral component, specifically in response to emotions, according to Justin Sundgot-Smith, a psychologist at the UCSB Student Health Service Alcohol & Drug Program.

People sometimes turn to social media because it helps them avoid having to deal with or process certain difficult emotions related to school or personal relationships, Smith said. The downside is that avoidance only serves to exacerbate these emotions.

What makes social media potentially addictive is how using it acts on our brain by creating “feel-good” neurotransmitters like dopamine. In that way, social media is very similar to other types of substance abuse, such as drugs or alcohol, Smith said.

During the pandemic, he started working with a lot of students who struggled with distraction and unhealthy screen use. After researching the topic, he created the Digital Wellbeing Group, which offers weekly group counseling sessions as a more “concerted, organized approach” to helping students manage their screen use.

Smith said that he feels hopeful about the future and our ability to mitigate and manage our relationship with digital media, as there has been more effort to mobilize and make an organized effort to combat this problem.

“You’re starting to see more programs offering either counseling or education surrounding this topic, [which is] more widely known now,” said Smith.