Jennifer Sor

Arts & Entertainment Editor

After years of being predominantly white, meet the new face of Hollywood: a bizarre, multiracial cyborg. She’s everywhere — your TikTok feed, mainly — sprouting plump lips on a thin face, thick lashes but fine body hair, blonde locks and tanned skin that seems to contradict it. She’s exotic, boasting genes from Africa, Asia, and Native America — as if, under pressure to be more diverse, the media pulled features from every race, manufacturing a celebrity that somehow looks like everyone and everything.

It’s Addison Rae glopped with self-tanner; it’s Ariana Grande with lightened skin and Korean eyeliner; it’s Kim Kardashian in Fulani braids and looking offensively bronzed on the February cover of Vogue. She’s poised, robotic, a racial fish — someone, usually white, who has altered their appearance to imitate another race.

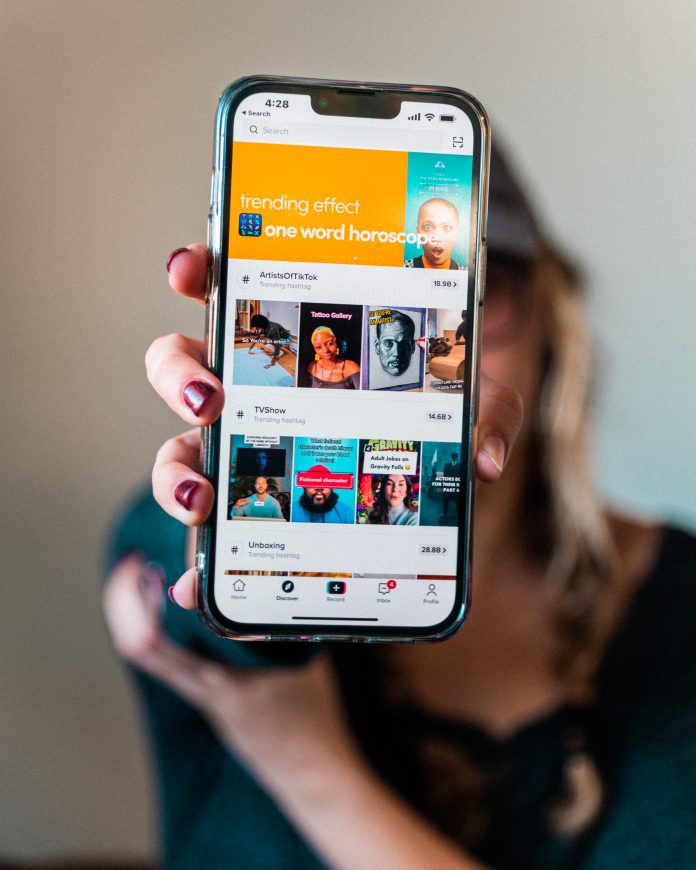

Rather than overt whiteness, it’s racial ambiguity (a “cyborgian look,” Jia Tolentino describes in her New Yorker piece) that now dominates the media, the product of a decades-long crusade to say, look, we’re really not as white as you think. On the surface, our obsession with ethnic ambiguity appears to be more inclusive: television, TikTok, and other forms of entertainment are no longer ruled by a uniform Americana, but instead, an appreciation for other cultures. Such, at least, seems to be the excuse for celebrities who take part in racial fishing.

“I love Black culture,” said Jesy Nelson, a white musician accused of darkening her skin and altering her hair to look Black in her “Boyz” music video. “I just wanted to celebrate that.” Kim Kardashian similarly defended putting her hair in Fulani braids, calling it an inspiration rather than an appropriation of Black hairstyle: “I know the origin of where [Fulani braids] came from and I’m totally respectful of that. I’m not tone deaf to where I don’t get it.” she said.

It is, in flagrant degrees though, tone-deaf. Blackfishing, for one, bears remarkable similarity to Blackface, a racist costume tool used by white actors to play Black characters. To pose as Black not only denies that history, it does so with a brush of selfishness: I like it, so I did it. (The lyrics of Ariana Grande, who has been accused of Asian-fishing and Blackfishing, come to mind). The media is a me-market, and if there’s some virtue in looking Black — even if it hasn’t always been that way — why not get some of it for yourself, especially if you have the resources to do so?

While it may stem from an appreciation of another culture, the emulation itself only highlights the disparity in power between those who are forced to live the Black experience and those who can change their appearance at their convenience. A white celebrity can go to a salon, fork over some cash, and walk out a more ambiguous (and profitable) creature. It’s easy, a racial fetish that disguises itself under capitalist self-creationism.

The problem also lies in its misdirection: there’s a difference between recruiting diverse stars and having stars front an image of diversity; in other words, manufacturing racial ambiguity for their own gain. After all, it’s Nelson who reaped the profits of her music video, not someone who actually has a dark complexion.

Although it has the outward appearance of being accepting (or, as Kim Kardashian claims, “inspired”) by other cultures, racial fishing hasn’t changed the fact that white creators still reign supreme in every form of American media, encompassing 90 percent of the Academy roster, 90 percent of television showrunners, and nearly all of the highest-paid TikTok influencers. So far as the camera is concerned, being white still is the beauty standard. Only now, the media is filled with white celebrities who have been able to profit off emulating another race.

This emulation is nothing new, Hollywood lugging with it a guilty and long-nurtured fixation with exoticism — specifically, roping white actors into playing an ethnic, exoticized role. Elizabeth Taylor played Cleopatra in the eponymous 1963 film, her white complexion unabashedly rocking an Egyptian headdress.

Gal Gadot, another fair-skinned actress, played the Amazonian star in the 2017 “Wonder Woman,” with plans to also star as Cleopatra in a future film despite objections that the role should go to a Black or Middle Eastern actress. Since the creation of media, foreign cultures have been abstracted, pulled into distillate parts — skin, clothing, hairstyle — and invariably given to white actors to profit from.

It makes it clear why Black and other audiences take offense to these images. At its core, it’s a form of deconstruction: a stripping of your own skin and watching someone utilize it for an opportunity you’ve never gotten. The fact that it’s now a beauty standard is irrelevant: emulating abstracts a person as a step stool in someone else’s rise to fame, draped with the skin and hair they recognize as their own.

The problem lies not in the experience of those playing those roles, but the experience of those watching it. Instead of hiring white celebrities to stand in as diverse, the media should start looking for people who fit the bill.