Janice Luong

Staff Writer

If there is one thing to be learned from this pandemic over the last year and a half, it’s the health care inequality the global south is currently facing.

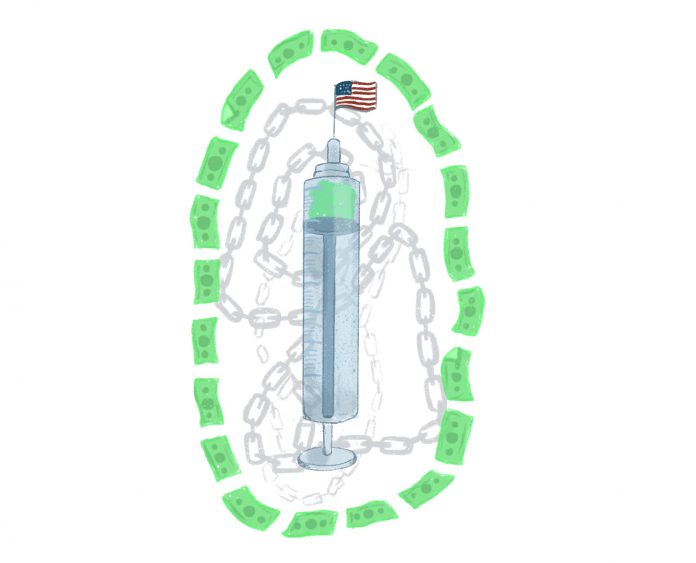

The world is in a vaccination race with COVID-19 — however, with over 80 percent of vaccines being distributed to wealthier countries, poorer countries are being left behind. Just 0.2 percent of the vaccines are administered to poor countries, leading many to criticize it as inaccessible, mirroring the wealth gap around the globe.

Currently, 46.04 percent of the United States population has received one dose, whereas poorer countries like India only have 9.99 percent, and less than 1 percent of Guinea has had their first dose. In Santa Barbara County, 52.09 percent of residents have received their first dose of the vaccine.

According to Tedros Adhanom, the general director of the World Health Organization (WHO), one in every four people in wealthier countries has received the COVID-19 vaccine, compared to one in more than 500 people in poorer countries. If this inequality continues, it is predicted that it’ll take at least two years for poorer countries to inoculate the majority of their population. This threatens the global population as the death toll is quickly increasing for poorer countries while the virus continually mutates.

“The world is in a vaccination race with COVID-19 — however, with over 80 percent of vaccines being distributed to wealthier countries, poorer countries are being left behind.”

Some mechanisms that wealthier countries have — which allow them to have a surplus of vaccine supplies — are export control and the ability to deal with pharmaceutical companies. When there is an increasing supply of the vaccine, export restrictions may be placed to prevent vaccines from leaving borders.

In an interview with The Bottom Line (TBL), distinguished professor of global studies and sociology, Jan Nederveen Pieterse, said there are three main challenges in global vaccine distribution: intellectual property, vaccine production, and vaccine sharing. The biggest hurdle he shared is the intellectual property of vaccines as it dictates the course for vaccine production and eventually how the vaccine can be distributed.

Professor Pieterse spoke of how the conversation surrounding vaccine sharing is in response to the idea of wealthy countries having a surplus of vaccines, and that they have more than they need. “How can we decentralize vaccine production?” Pieterse asked, suggesting that timing and production are still big obstacles to effective distribution.

Patents are another major obstacle. Recently, the U.S. has proposed a temporary patent waiver for certain obligations under the agreement for COVID-19 vaccines. The waiver would allow other countries to produce the COVID-19 vaccine without facing any legal action from patent holders for the vaccine. As a result, supply would increase overall. Professor Pieterse explained if these waivers succeed, developing countries can also produce it.

““How can we decentralize vaccine production?” Pieterse asked, suggesting that timing and production are still big obstacles to effective distribution.”

“Because of patent issues held by pharmaceutical companies, India and other countries cannot use their production capacity because they don’t have the right to produce it,” he explained.

Experts say that the longer it takes for the world to be vaccinated, the higher the chance vaccines will lose efficacy due to ongoing variants. The negotiation goes like this: countries would give pharmaceutical companies billions of dollars for research and development in exchange for priority access to vaccines.

As Santa Barbara Country and other locations in the U.S. continue to vaccinate, the conversation surrounding the ethicality of our priority access grows as the virus continues to spread.