Ladann Kiassat

Contributing Writer

If you had stepped on campus in late February, life, although chaotic, would not have seemed out of the ordinary. It had already lost the lackadaisical rhythm and carefree pace of the early quarter — a time before students had been bogged down by the weight of ever-increasing academic, social, and extracurricular commitments. Yet the flurry of students rushing about as their schedules become increasingly strained is a stressful — albeit familiar and oddly comforting — aspect of the college experience.

With the emerging news about COVID-19’s spread, the change was subtle. At first, it did not impact regular living. It was seemingly a far-off concern. So gradually did its grip tighten on our lives and psyches that by the time COVID-19 forced students off-campus, we could hardly believe that we were in the midst of a historic pandemic. Our shared presence on campus was found to be a privilege taken for granted. Classes became remote. Our friends became remote. And, the memories of a collegiate vita activa became more remote than ever.

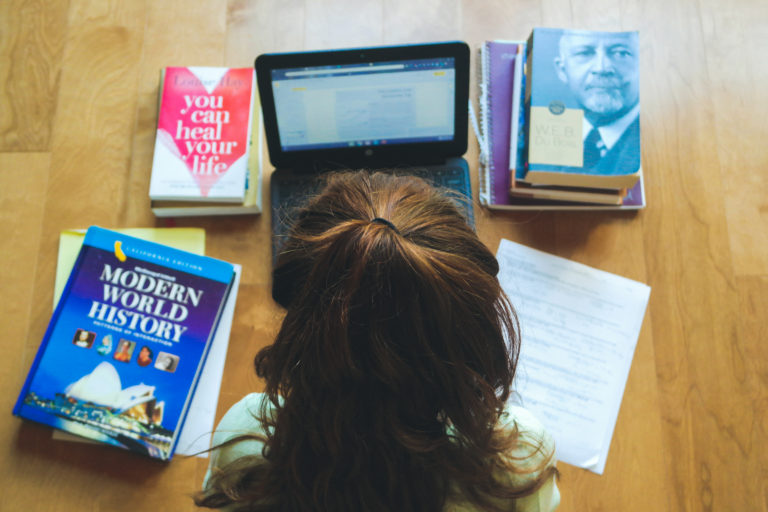

As the reality of remote education began dawning on students and faculty, the thought of diving headfirst into the daunting new quarter felt less and less like an opportunity to start over and more of a burden about the uncertainties of the future and quality of our education. The devastation that is unfolding before our eyes can only best be described through the student scope.

Students from a variety of backgrounds sat down for interviews with The Bottom Line (TBL) to discuss how they are feeling the harsh wrath that comes with a remote style of living. Alexandra Perez, a second-year political science and history of law double major said in an interview with TBL that she feels an “increasing amount of difficulty focusing,” and is concerned that professors are “assigning more work” as a means to overcompensate for remote education.

There has also been scrutiny over internet accessibility. Daniel Segura Esquivel, a third-year sociology major with a minor in education, told TBL that a hefty obstacle with remote education at home is “wifi stability.” “Although the school wifi is unreliable at times, it is a lot stronger than at home wifi,” which is a costly factor when taking timed examinations online, Esquivel explains.

Esquivel, who is a current off-campus senator for Associated Students, also reports feeling “left in the dark” by administration during the shift to remote learning. He told TBL that he wanted “emails that solidified course of action,” rather than a stream of meaningless emails that were not thoroughly explained.

Another point of concern for students is access to required course texts. Ava Korgosha, a third-year political science and psychological and brain sciences major, describes the burden of “professors not being lenient with expensive textbooks during this time” when resources like “free and for sale are not readily available for students facing financial difficulties.”

Although most students report feeling overly stressed, others are adapting to remote education quite well. Luca Angeleri, a first-year physics major, remarks, “In some ways, remote learning has been easier. Being able to pause the lectures, and go back helps me understand the material” in greater depth. Marissa Mazurie, a first-year mathematics major, describes her remote experience as “hard, but flexible” as long as she stays on top of her work and communicates with her professors.

“Since everyone is in the dark during this online education thing, my professors are responding and being accommodating,” she says.

During these unfortunate circumstances, it is safe to say that adapting to remote education is difficult for many. Although the light at the end of the tunnel seems distant, we can only hope that UC Santa Barbara’s administration and students slowly begin to adapt to this culture in order to make the best out of a terrible situation.