Sofia Lyon & Nathan

Staff Writer & Contributing Writer

“Western culture” is a vague term often seen in academic environments. However, it is difficult even amongst scholars to identify which cultures and peoples are included within the distinction of “western.”

While much of it is explainable via the rigid reality of academia, the distinction of “western” culture does speak to a greater understanding of world culture. What it ultimately speaks to are the origins of philosophies which dictate diverse ways of life across the planet.

Thousands of years ago, “the West” was born in Greece with all of its advancements in culture and science. Greek plays and myths, the architecture of the great temples, and even the basic schools of thought all survived long past the fall of the ancient Greek city-states. They moved westward with the next great civilization, the Romans, and, after Rome fell, continued to move even further west until they reached America.

“The West” is vague, but purposefully so. It’s impossible for a single word or term to prove description enough for content as broad as culture, architecture, basic thinking, storytelling practices, rules for law and governance, and so on and so forth. By being vague, “the West” is able to serve as the blanket term used for all of it, and provides easy distinction from the other main school of thought in the world, “the East.”

Both schools of thought have drastically different ideas on how the world and society should be governed. “The East” is far more communal, and far more reverent of the elderly. “The West,” on the other hand, is wildly individualistic, pushing for each person to carve out their own mark. Family names became less important in the west because of this.

Thus, “western culture” seems to be a somewhat arbitrary distinction used across academics to describe ideological, cultural, and ethnic uniformity amongst European and derivative nations.

Of course, this distinction does not account for the entire picture of typically “western” nations, namely the problem of Eastern European countries, who often can be seen as outliers. They are excluded from the engagements of Western Europe, and also have endured much cultural assimilation from Mediterranean and Middle Eastern states.

So, we can acknowledge the shortcomings of the term pragmatically. What was also previously pointed out is its use in separating “the East” from “the West” — a separation almost solely based on historical development of technologies and differences in major philosophical schools which govern political and cultural mentalities. Eastern philosophies focus significantly on collective good, whereas Western philosophies are centered on good for the individual.

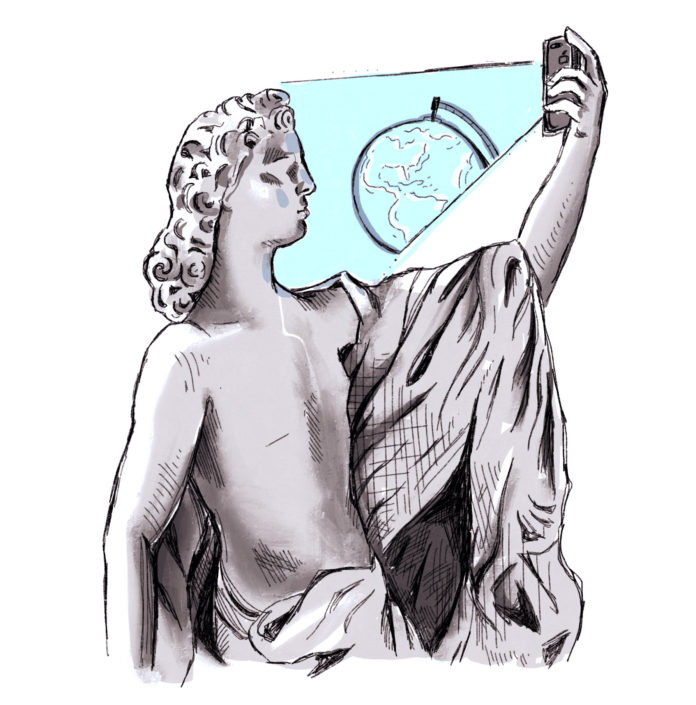

These fundamental philosophies ultimately guided variant cultural development. For instance, it would seem that the advent of the American dream is a result of “the West’s” tendency towards individualism. Similarly, cultures of vanity, celebrity, and social media spun from the same self-interested nature of Western thought.

Western culture does not describe any specific group or belief, but instead it describes tendencies within cultural thought and practices, tendencies which favor the plight of the individual rather than the collective. It is a distinction which should not be given more depth than it is worth — an academic dichotomy. It speaks to greater separations in the development of world culture.