Frances Castellón

Managing Editor

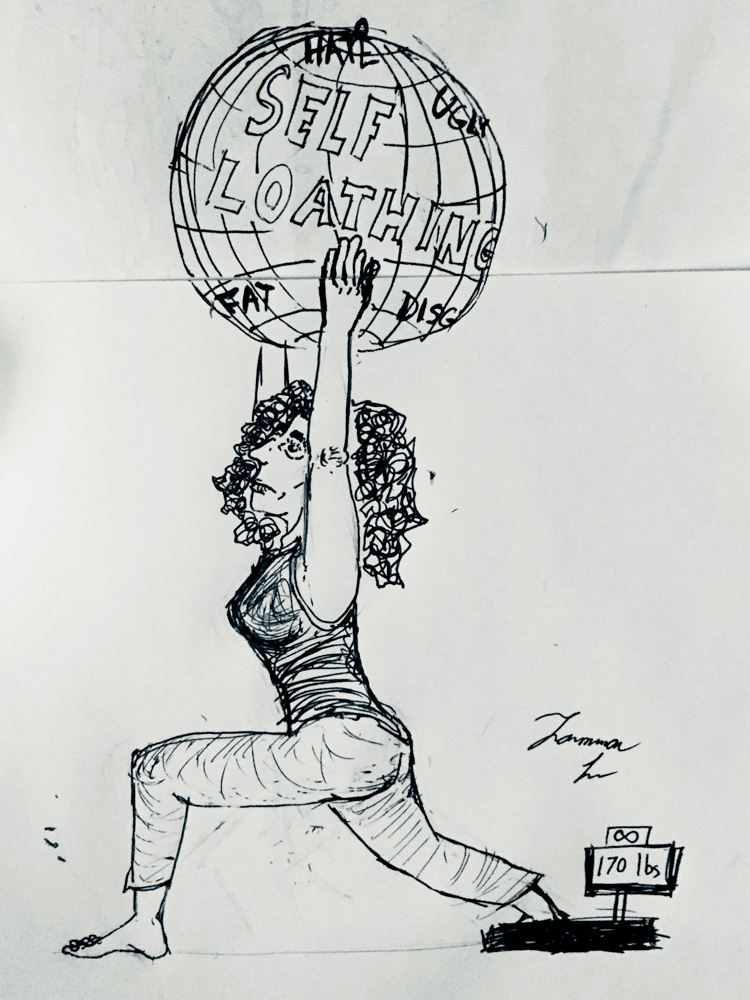

For the past four years, I have been struggling with an eating disorder despite being surrounded by friends and family that could have supported me. While it first began as a fear of weight gain, my disorder soon evolved to be a reward for doing well academically. If I had realized sooner that I could have received support from friends and family, I could have prevented myself from experiencing the mental and physical pain I endured.

About a month into my first year, I changed my eating habits to please a friend. She repeatedly commented on what I ate, how much, how often, and how I looked. Instead of confronting her about it, I did one of the most destructive things I could have done to myself: I believed someone else’s “truth.”

By the end of fall quarter, I was not only hiding my thin frame with a smile, and layered and striped clothing, but had also lowered my calorie intake to 300-500 calories a day. I occasionally allowed myself to eat dinner with my roommates, but the shame I felt after eating never wavered.

To put it simply, I was terrified of gaining weight. I couldn’t bare to look at myself or be around others out of fear that they would be just as disgusted by my body as I was. It would take me at least half an hour to step outside of my dorm, and I couldn’t look at myself without seeing the roundness of my face or the wideness of my legs.

Instead of reaching out to the support system I knew I could have had, I didn’t ask for help because, despite the mental and physical pain, I couldn’t stop. It was euphoric. I felt proud, as if I was doing something worthwhile the more I hurt myself, because if I didn’t eat, then I didn’t hear the disorder coaxing me to restrict my intake or starve myself. I felt like I was getting better. If it meant that my body and my mental health had to suffer, then so be it.

I was so miserable that I considered dropping out of school. I was scared at the thought that I would have to return to the dorms with a meal plan again because the dining commons rarely offered food that I was comfortable eating. I would relapse days or even hours after committing myself to getting better because I was surrounded by food that prevented me from making any progress.

I believed that being in an apartment and in control of my food would help, so in fall 2015, at the start of my second year, I found myself moving into Santa Ynez. I found myself incorporating foods that I had previously banned, but it was only because my disorder had developed into something else: punishment. If I didn’t get the grades that I wanted or was behind on readings, then I would blame myself and felt that I deserved to starve.

Because food served as a reward, I would spend hours in the library, prohibiting myself from eating until I felt like I deserved it. Naturally, with all of the studying I saw my grades improve, which only convinced me that I was getting better. So I kept up with the endless hours spent in the library, while I silenced my stomach growls with coffee.

For almost two years, I twisted the disorder in such a way that I made myself believe that I was getting better, even though I couldn’t stick to recovery for more than a week. However, in September 2017, I decided I would give it another chance and managed to stay in recovery for about 18 weeks. A few exciting things happened: I found solace in cooking and actually looked forward to eating; I was beginning to love my body again; and at the end of the quarter, I was able to say that I made the Dean’s Honors list and that I took care of myself. But perhaps the most exciting thing was that when I thought about relapse, it didn’t scare me as much anymore.

So when I relapsed at the beginning of winter quarter, I was obviously disappointed, but I used the previous 18 weeks as a reference. If I was able to stay in recovery once, I could do it again. And I have. Though not often, there have been moments where I catch myself in the mirror and I see my body as it really is, not as my disorder made me see it. I’ve even caught myself feeling surprised by my thin frame and thinking that I could use a little more weight. In those moments, I’ve felt my heart relax.

Although I should have known from the beginning, I have now learned that it’s okay to eat and that I have to be patient with my recovery and forgive myself for my mistakes. I have come to understand that it’s not selfish to give myself the same love I give to others.