Kristie Chairil

Staff Writer

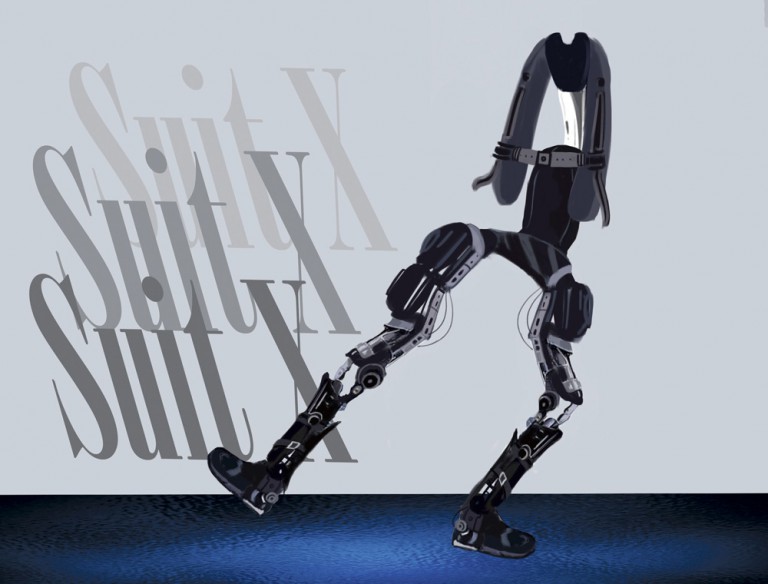

According to the National Institutes of Health, there are millions of motor-impaired Americans who cannot perform basic everyday routines without assistance. However, with a new robotic exoskeleton unveiled on Feb. 1 by Berkeley-based startup suitX, they may be able to walk independently — at a lower cost and weight.

The Robotics and Human Engineering Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley have developed an exoskeleton, called Phoenix, that costs $40,000 and weighs a relatively light-weight 27 pounds, which is $30,000 less and 23 pounds lighter than the current exoskeleton on the market, ReWalk. It enables users to walk a maximum speed of 1.1 mph and the battery pack, worn as a backpack, functions for up to eight hours.

According to Berkeley News, the exoskeleton works at the command of buttons on each crutch and actuators located around the hips that transform electrical signals into movement, allowing users considerable independent control of their walking. The apparatus can also adjust to people of different heights as well as their specific needs; for example, it can adjust to a shorter person’s problem on just their right knee.

“Robots are now integrated into common medical practice,” Tyler Susko, a University of California, Santa Barbara mechanical engineering professor, said in an interview with The Bottom Line. “UCSB’s own Yulun Wang was a pioneer of robotic surgery which is now a fairly common and effective form of minimally invasive surgery. Rehabilitation robots have found their way into clinics, and in 2010 were given one of the highest possible ratings for treatment of stroke by the American Heart Association. Robots are even rolling around in the hallways of hospitals delivering medications to patients.”

Professor and suitX CEO Homayoon Kazerooni says that although this project cannot reverse the effects of spinal cord injury or mobility-impairing disease, it can “postpone the secondary injuries due to sitting” in a wheelchair and give “a better quality of life.” According to Fast Company, the goal is to bring about extensive at-home patient use, which would encourage increased personal independence.

“The Phoenix follows a long line of robotic exoskeleton work initiated by UC Berkeley Professor Homayoon Kazerooni and his research group,” Susko said. “He is undoubtedly a leader in the field of overground exoskeletons. In my opinion, this type of work is an ideal depiction of the impact engineers can have on the world, reversing the effects of traumatic injury.”

Steven Sanchez, paralyzed by a BMX bike accident over ten years ago, was able to test the Phoenix. In an interview with U.S. Bionics, also known as suitX, he said, “I feel much more like myself, and humanlike, being in this device, being able to stand up eye-to-eye with somebody. It’s strange that this robot makes me feel more part of this planet than the wheelchair does.”

However, for all its lower cost, the device is still unaffordable for many, as it is uncertain whether or not insurance companies will cover it. Still, the distribution of these exoskeletons to rehabilitation clinics and hospitals will gradually increase people’s access to mobility assistance.

Dr. Kazerooni says that his main goal going forward with Phoenix’s development is to create a version of the exoskeleton for children born with neurological disorders. Training the muscles earlier of those who might lose their motor skills later is crucial. The Phoenix could also potentially help treat victims of stroke or other nerve paralysis.

Phoenix is not the first of its kind; the military has also prototyped exoskeletons to help soldiers with speed, agility and strength in carrying heavier loads on the battlefield. As these technologies unfold, the human engineering field brings hope that these devices will increase mobility and normalcy in the daily lives of millions.

UCSB mechanical engineers are also currently working on a walking device as well. “I’m launching a UCSB lab right now, Lab d4H (design for humans), to do similar work,” Susko said. “A team of UCSB mechanical engineering seniors are currently working on an assistive walking device for people with supraspinal injuries, and I am hoping to leverage a partnership at Cottage Rehabilitation Hospital to come up with ways we can further improve lives.”