Giuseppe Ricapito

IV Beat Reporter

Photo by Giuseppe Ricapito, IV Beat Reporter

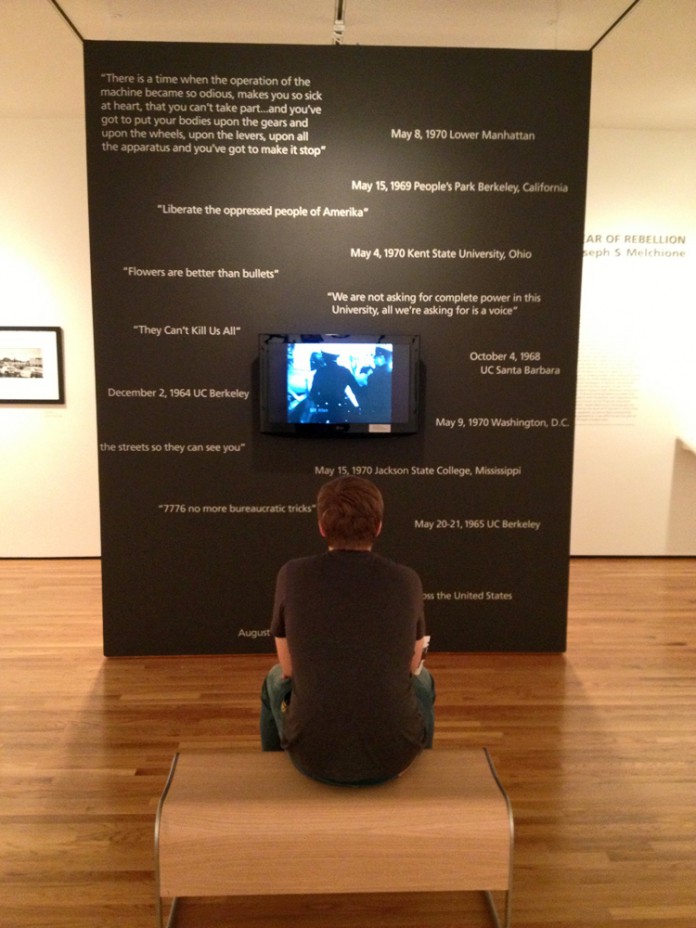

“Year of Rebellion: The 1970 Isla Vista Riots,” featuring vintage photographs from Joe Melchione, is a featured exhibition at the Art, Design and Architecture Museum at University of California, Santa Barbara. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, UCSB alumni, former faculty, community members, and students congregated at the Little Old Theatre for a panel discussion on the legacy of Isla Vista’s seminal militant social-activist movement.

A short film featuring Joe Melchione, who passed away in 2012, preceded the discussion. While presenting an overview of his photography, which charts the 1970 movement from the burning of the Bank of America building to the incursion of the National Guard, Melchione offered both facts and insight on turbulent social protest.

“I really want people to see a part of Santa Barbara’s history that I think has been lost or shrouded in myth,” said Melchione, the photo editor for the 1970 UCSB newspaper, El Gaucho.

“I want people to understand that group action, collective action, does work, and if you say something long enough and loud enough people will finally listen,” said Melchione. “Hopefully this show will start some thinking, some dialoging, about the ability to bring about change.”

Melchione’s snapshots, taken on a fully manual film camera, capture moments of violence, unrest, and demonstration, charting the shifting chronology of outbursting rebellion to peaceful, sit-in protests.

Richard Flacks, the panel moderator, was a UCSB sociology professor in 1970 and active in the burgeoning student movement.

“University authoritarianism united a lot of students and alienated them from the status quo,” Flacks said. “There was more freedom in people’s lives [back then] for figuring out what to do in terms of social issues.”

Melchione noted that the major riots occurred from late February through June of 1970, but many events led to the culmination of mass protest.

“In 1969, 1970, a lot of events kind of coalesced: ongoing protests by minority students with respect to the universities minority policy, big complaints about absentee landlords in Isla Vista, disputes with the Sheriff’s department about drug enforcement policies, liquor enforcement policies in Isla Vista, and—obviously and also very importantly—the growing, growing opposition to the Vietnam War,” Melchione said.

The photographs range from symbolic images to portraits of human sentiment. Some highlights are a burning, overturned Sheriff’s car; a razed Bank of America sign; a disillusioned young police officer; and a crowd of students listening to a speech by protestor Jerry Rubin. Overall, the exhibit and panel discussion touched on many complex topics surrounding the upheaval: the denial of tenure to UCSB professor Bill Allen, the demonstration and storming of the Administration Building (now Cheadle Hall), the accidental shooting of a UCSB student by a Sherriff’s Deputy, the calling in of the National Guard, and the partial closure of I-101 by over 5,000 student demonstrators.

Of the 50 total people at the forum, only about one-fifth were actually students. The majority of the attendees were about 60 to 80 years old, and had personal memories of participating or observing elements of the rebellion.

The presentation then shifted gears to a panel consisting of Becca Wilson, former editor of El Gaucho; Mick Kronman, an active social dissident in 1970; Doris Brigante, married to demonized local Sheriff George Brigante; and Yonie Harris, a founding member of the Isla Vista Food Co-op. Though the photographs and memorabilia were the impetus for the panel discussion, their personal testimonials broadened the scope of the history and illustrated key elements of the rebellion’s story.

Wilson remembered vehement criticism from both school administrators and right wing activists, but like many of her peers, she perceived injustice in the treatment of university youth.

“I felt a moral obligation to champion the movements that were going on,” Wilson said. “We have a responsibility to tell the other side of the story. It was a difficult position to be in.”

Kronman, between his (disputed) memories of Molotov cocktails, weaponized bricks, and the presence of firearms, also attested to the distinct social role of the school newspaper throughout the year of protest.

“The El Gaucho was the heartbeat of that movement,” Kronman said. “That’s really the role of journalism, not necessarily be biased one way or another, but be integrated with community interests and to be a mouthpiece for community interests.”

The panel also recalled leaflets and pamphlets emblazoned with closed fists of solidarity—printed at a moment’s notice at the original Kinko’s copy store in downtown Isla Vista—which dictated attitudes such as “WE ARE ALL YOUNG. WE ALL WANT CHANGE.”

The role of journalism and dissemination of information were crucial organizational tools in the 1970s, and student attendees were keen on finding a modern comparison to contextualize these endeavors.

“Social media … seems to be the modern day way of community, of networking and creating a cohesive movement,” said Kronman, referencing the social unrest of the Arab Spring.

In response to Kronman, a crowd comment postulated that modern social media might produce the same effect of insularity that hampered the 1970s movement.

“The social media now … it is so easy to just get locked into a little network of shared beliefs without cross checking, without being open to the other side,” said an attendee.

The 1970 “Year of Rebellion” is an unprecedented event in Isla Vista history, but in the minds of present day students, its legacy is nebulous at best. The few student attendees at the panel expressed disappointment that few of their peers had come out to learn a crucial element in Isla Vista history.

Flacks suggested that revolutionary elements were still present in modern day Isla Vista, but insisted that the 1970s rebellion was not a perfect comparison.

“I actually think there’s a lot of student activism now and a lot of it is creative—one difference is [that] there isn’t necessarily one unifying tremendously threatening matter that a lot of students need to know,” Flacks said. “So I would rather people didn’t compare so much why did they do all this then, you just do what’s creative and makes sense at the time.”

Moizes Ponce-Zepeda, a fourth-year history major, stressed that the knowledge of “economic decisions” and “houselessness” can guide a student’s conscience on issues of social justice.

“In the back of a lot of students minds, in the back of a lot of individuals minds, whether you’re working or your learning, you always have to keep that consciousnesses in mind,” Ponze-Zepeda said. “I think that’s something that brings the spirit of rebellion to the circle.”

The Occupy movement was a recent manifestation of a global protest coming to bear in Isla Vista. But in the modern environment of polarized political opinion, according to The Santa Barbara Independent, it not only failed to generate widespread support, but was also hampered by police intervention.

Flacks, though disavowing of a direct comparison between the past and today, expressed positivity for modern day Isla Vista.

“Student activists now may hear what happened then and say ‘well, we’re still fighting those battles,’” Flacks said. “Even though it seems very different, still there are issues.”

Looking outward from the dais to the group of students huddled in the rear on the theatre, he finished, “The potential power of students now is far greater than it was then, in certain respects.”

Photo Courtesy of www.joemelchione.com

Comments are closed.