Giuseppe Ricapito

Staff Writer

An album titled “The Psychedelic Sounds of the 60s and 70s: Re-mastered and Reissued” needs to be released, because there is a psychedelic rock revival currently permeating the ears of the nation. Influenced by classic recordings from Pink Floyd, the Grateful Dead, The Doors, Jimi Hendrix and the Jefferson Airplane, it draws from the stylings of blues, folk, soul, and punk to generate a new sonic revolution. In the 21st century, the magical mystery tour rolls on.

William Blake famously wrote, “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” This quote captioned the psychedelic era, contributing to the titles of both Aldous Huxley’s book on the effects of mescaline and a revolutionary band fronted by Jim Morrison. The acid culture has prototypically experimented with various consciousness expanding drugs, including (but not restricted to) LSD, magic mushrooms, ayahuasca, and peyote. The psychedelic perception is based on the linkage of the psyche and the body (by a strange paradox) in moments of their disassociation, an individual gains wider awareness.

“Music and the Psychedelic Mind,” a Pitchfork documentary on psychedelic culture, charts the chronology of rock n’ roll through the compositional advancements of the present day. Charles Grob, M.D., Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics at the Harbor UCLA School of Medicine, discussed the remedial roots of LSD. In the 50s and 60s, “psychedelics were considered the cutting edge of psychiatrics and neuroscience research…with Tim Leary’s involvement and some others, suddenly the secret was out of the laboratory and into the mainstream culture,” Grob said.

To Tim Presley of White Fence, 60s psychedelia was the “child” of earlier forms such as jazz and the blues. Buoyed by mind-expanding substances, music garnered these influences and developed as a function of revolutionary social change.

The classic music of the psychedelic heyday was rooted in social opposition, a countercultural vibe that resonated with baby boomers, college students, anti-Vietnam protesters, and Civil Rights advocates. The music was not exclusively political, but in a climate of diverging generational identity, these new sounds flourished hand-in-hand with the changing American landscape. Evolving through the present day, psychedelic music and social commentary can be mutually exclusive. Instead of politics, the primers of the collective consciousness seem to weigh on the side of identity, paradox, and social preservation. These heavy philosophical themes are meant to compel entertainment, joy, and self-reflection—pleasurable in any moment and heightened in a state of delirium.

Trippy music is everywhere, however. A drug culture of ecstasy, molly, and LSA accompanies Electric Dance Music (EDM) and its subsidiary genres. As a factor of individual preference, EDM arguably expands one’s consciousness just as powerfully as rock n’ roll can. The psychedelic rock revival is prefigured by traditional bands, rooted in festival origins such as Woodstock, Monterrey Pop, and Altamont. Vocalist, guitar, bass, drums (throw in an organ or an electric jug)—it’s an established performance art with professional concert artists expressing their craft.

April 25-28 marked the sixth annual Austin Psych Fest, a three-day festival hosted by the Reverberation Appreciation Society to celebrate the hallucinatory sounds of bands such as The Moving Sidewalks (featuring ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons), Warpaint, Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, and Os Mutantes. Psychedelic festivals are even cropping up in our own backyard—on Cinco de Mayo, the first annual Psycho de Mayo was held at the Yost Theater in Orange County. Featuring Black Mountain, Dead Meadow, and Dagha Bloom, it was decorated with an ornate and trippy Day of the Dead aesthetic. In a class among themselves, the groups at Psycho de Mayo and Austin Psych Fest are at the forefront of a rapidly maturing musical transformation, lighting the fire of a new generation.

Brooklyn duo Golden Animals played Austin Psych Fest following a desert circuit in Southern California. They’re slated to release a new album, “Hear Eye Go,” which expands on the harmonious blues from their debut “Free Your Mind and Win a Pony.” Described on their website as a “dead-ahead, no bullshit, loud, minimalist vehicle,” their music is a biting, nomadic hippie manifesto. On “Most my Time” lead guitar and vocalist Tom Eisner echoes a mind bending paradox, singing, “Cause I get most my light at night / Sink down to the height / Deep down to the flight / Most my time alone.”

So-cal psycho-surf rock band The Growlers, who will take the stage at University of California, Santa Barbara’s Extravaganza on May 19, have grown more prolific in the last year. Their new album, “Hung At Heart,” comes at the heels of “Hot Tropics, Are You in or Out,” an eight-part series, and their reclusive debut “Greatest Hits.” Their self-titled genre of “Beach Goth”—featuring a strange brew of Brooks Nielsen on vocals and Matt Taylor on grooving, bluesy guitar—is drawing followers far beyond their origins in Costa Mesa, Calif. “One Million Lovers,” the doting lead single from the new album, merges a swinging bass line from “Anstonio” Perry and Kyle Straka’s traipsing, rhapsodic organ. Nielsen intones, “One million lovers to choose from but no one like her / The only one for sure.” Their music blends perfectly with the accompaniment of manic, transposing music videos—some of the best include “Graveyard’s Full (Wilcox Sessions),” “Drinking the Juice Blues,” “Salt on a Slug,” and “What it Is.”

Australian neo-psychedelic band Tame Impala has broken into the rock scene with a far-out sound that blends influences from seminal bands such as Cream and Pink Floyd. Featured at this year’s Coachella, Impala’s new album “Lonerism” dictates the same foggy vocals, churning rhythms and opiate sound waves that brought their debut, “Innerspeaker,” to prominence. Featuring new cuts such as “Elephant,” “Apocalypse Dreams,” and “Feels Like We Only Go Backwards,” Tame Impala is recording psychedelic music that the public is greeting with receptive enthusiasm.

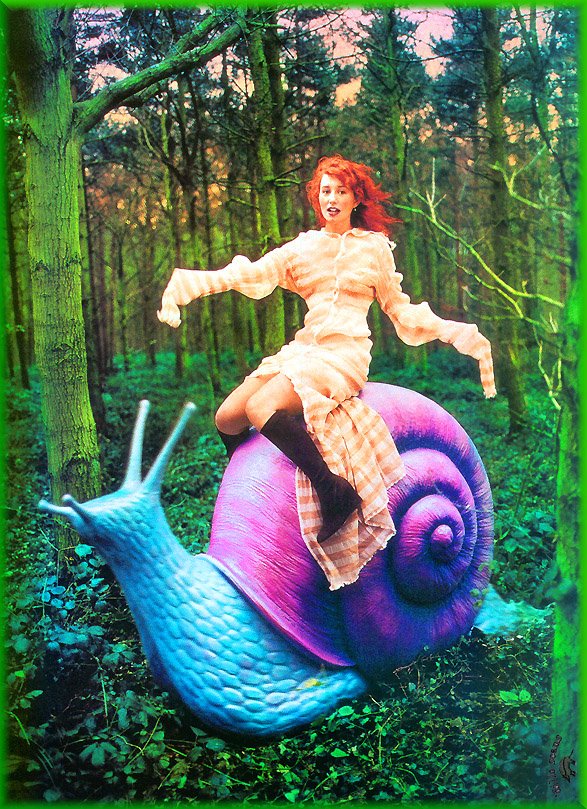

Psychedelic music has the quality of a cyclone whirlpool—swirling levels and empty spaces molding in chaos as the listener is drawn into the eye of the storm. Break down the phrase, and you have a broad genre that can encompass a diverse variety of musical themes, all of which relate to consciousness or its expansion. It recalls chaos and disorder; it is a collage of figures and icons, morphing multicolored lights, and oils modulating in abstract, interpretive forms.

When you gloss over the abstractions, you have music that can be surreal, frenzied, opaque, or lo-fi. Psychedelic music isn’t only for the mania and stasis of drugs, but those that enjoy both see it as hand-in-hand. In those moments where your mind finds itself in the cerebral poles of inspiration or depression, psychedelia rings true.

If you’re interested in more psychedelic sounds from both the past and the modern era, here are a few suggestions:

60s and 70s

1) “You’re Gonna Miss Me” – The 13th Floor Elevators

2) “Dominoes” – Syd Barrett

3) “Comanche” – Jorge Ben

4) “Pyramania” – The Allen Parsons Project

5) “Over, Under, Sideways, Down” – The Yardbirds

Modern

1) “Black Crayon” – Christian Bland and the Revelators

2) “The Love Between” – White Fence

3) “Shadows in the Night” – Night Beats

4) “Grim Reaper Blues” – The Entrance Band

5) “Can You See?” – Thee Oh Sees

Photo courtesy of everystockphoto.com