Alice Dehghanzadeh

Opinions Editor

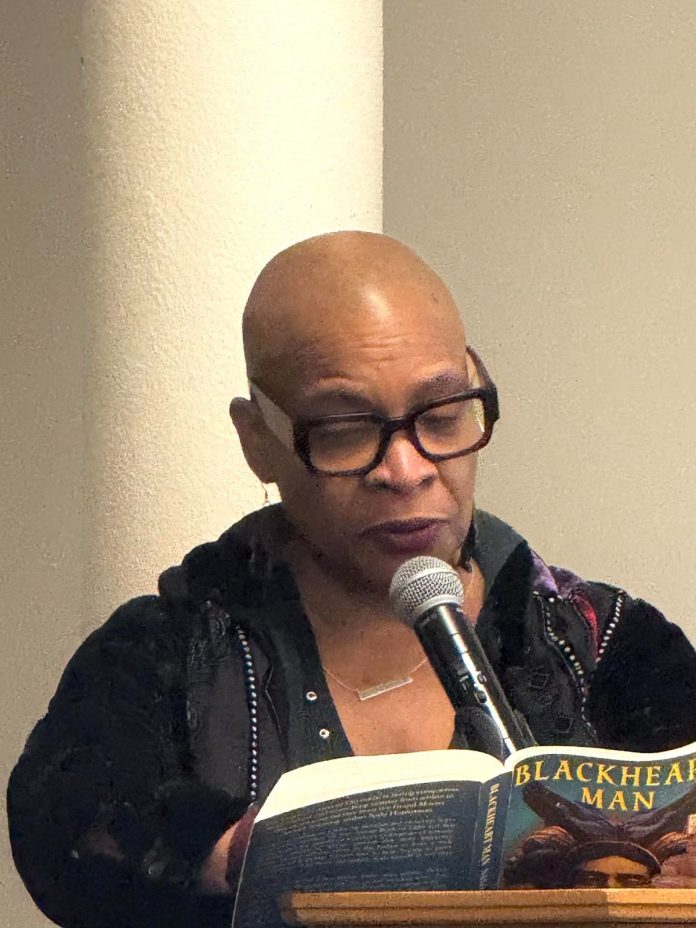

On Feb. 21, the greatly admired author Nalo Hopkinson visited UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) to discuss her work, themes of identity and placement, and the writing process. With popular works such as “Midnight Robber,” “Brown Girl in the Ring,” and recently released “Blackheart Man,” Hopkinson has been named a Damon Knight Grand Master in 2020 for her contributions to the science fiction and fantasy realm. She is currently a professor in Vancouver, British Columbia, and has previously taught creative writing at UC Riverside.

Hopkinson’s Caribbean roots are what guide her writing of space and identity. “I’ve lived in the Caribbean, so it was easy to pull from there from memory,” she shared. This grounding element is evident in her writing that often pulls from Afro-Caribbean mythology and folklore. One of her consistent inspirations is the water, as mermaids and river deities play crucial roles in some of her stories. “I’ve always loved the water, especially the ocean,” she commented, “I was drawn to the riveting deities … I’m also interested in representations of the body and in honoring our bodies in all sizes and shapes.” She holds a particular fascination with fluidity, whether that be through identity or place.

Not solely an author, Hopkinson has also delved into the world of sculpting, creating her own statues by using things she finds from around her house as a complement to her literary work. She confirmed that she “finds it easier [than writing], and it’s soothing and feels affirming,” proving that storytelling can go beyond the page to be a visual representation as well.

Hopkinson later compared the art of revision to sculpting, highlighting how a first draft is just a first draft. “I think of that first draft as going down to the riverbank and collecting some clay,” she explained, “you don’t yet have a pot. You take it back … you don’t yet have a pot. You pull out the sticks and stones … you still don’t have a pot. You have to start working it, then shaping it, and then firing it.” She revealed that revision is a crucial step in crafting a story that readers won’t want to put down.

One of the most compelling moments of Hopkinson’s discussion was when she opened up about her neurodivergence and how it’s shaped her career. Diagnosed with Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) at 40 years old, Hopkisnon humorously noted how she “spent 40 years thinking [she] was mad, bad, and crazy; turns out [she] was only mad.” In addition to her ADHD, she shared that she has nonverbal learning disorder and fibromyalgia, which have impacted her way of writing and teaching. “We all have brains that are quirky, and we’re all supposed to pretend they work like everyone else’s,” she said, “Everybody’s always asking me about the rules of writing, and the rules depend on your brain. You get to make them.” She went on to say that her openness about her experiences with her neurodivergence has only made students feel more comfortable to open up themselves, creating a safe, inclusive environment for them to speak about their own challenges.

In Hopkinson’s work, there are themes of sex and sexuality, which she views as fundamental to storytelling as “sex is everywhere.” Recognizing Samuel R. Delany as one of her literary touchstones, she emphasized the importance of free expression: “There are no bad words, you should be able to express yourself.”

Similarly, food plays an important role in her work, serving as a metaphor and sensory experience. She explained that “food leads [her] directly to history; food is history, food is memory.” Her attention to sensory detail enriches her storytelling, showing how detailed description can be just as important as character actions or development.

The art of collaboration has not always come easily to Hopkinson, and is something she had to learn while creating comics. “I used to hate the idea of collaborating,” she shared, that is, until she started to appreciate the craft. “Collaboration has to be about letting the other person’s work influence the whole piece and taking the risk that what comes out the other end is not what you imagined.”

Additionally, Hopkinson shared how writing is a cathartic process, and that, sometimes, throughout, she would discover new things about herself. When asked about the practices she takes when handling delicate and traumatic subject material, she emphasized the importance of a true support system. “If you’re an artist or scholar,” she said, “the people you have around you are important. Do what you can to choose them carefully.”

Nalo Hopkinson’s visit to UCSB was a powerful one to attend and highlighted the importance of storytelling as a tool of resistance and reflection. Her words left a lasting impression, guiding audience members to navigate the world with curiosity, care, and a willingness to take in the unexpected.